Gathers Event Platform

For my senior year at the University of Southern California Jimmy Iovine & Andre Young Academy, I partnered with Clayton Barnes to work on our year-long thesis project– Gathers. Our program has us dedicate most of our fourth-year schedule towards developing a single, focused project.

Each Academy degree culminates in a powerful capstone course called The Garage Experience (Gx), which offers students the ability to do a deep dive into the development of innovative projects, leading to operational prototypes and viable enterprises, as well as proof of concept for advanced student research. Guided by expert faculty and field-specific mentors, capstone courses comprise invention, exploration, experimentation, and innovation as students work through project labs, workshops, demos, and formative and summative critiques. - via USC IYA

After Clayton’s experience working at CloudKitchens, we wanted to dive into the transformations of the restaurant industry. So, we set out to better understand the current landscape of food experiences and how people engage with food. To do this, we began by conducting a diverse research initiative. We planned to find and understand problems in the industry before we could ideate any product. We landed on Gathers, a software platform to help independent chefs, supper clubs, and event hosts run their operations. The software is a web application providing ticketing, financial tracking, and customer relations management services. As the second pillar of the software, experiences were listed through a consumer-facing page where they could book reservations. By working on the client and customer sides of these dining experiences, we effectively played the role of a two-sided marketplace.

Research

To initiate our thesis project, we set out to look at a variety of industry players, people, and services. We spoke with :

- Delivery-only restaurant

- Delivery services

- Private chefs

- Tastemaker consumers

- Small restaurant owners

Our professors also guided us better to understand the industry’s economics through more formal research. Some notable publications that drove our early decision-making included Strategies for Two-Sided Markets, Opening Platforms: How, When, & Why?, and The Food Revolution.

We also tried our hands at a variety of first-person experiences in food. I signed up as a Postmates driver to better understand drivers’ daily work journeys. Around this time, Clayton and I began to pick up on a trend we saw in major metropolitan areas: the supper club. Through the networks we grew at the time, we started to compile a list of non-official restaurants hosting “experiences.” Often, these began as fun projects for the chefs but grew popular among the attendees. Notable supper clubs included Pith, Maru, and Paladar.

Stakeholder Insights

The emergence of supper clubs fascinated us, and we found it an under-documented trend. So, we dug in. This became our initial customer group. We specifically targeted individuals who were hosting events themselves. One of our initial users, H Woo Lee, ran dining experiences in LA. H Woo, along with other small chefs, asked for tooling to manage the inflow of ticket revenue and track the back-of-house costs associated with running an event. You may have heard of H Woo, who has since become a celebrity TikTok chef. We talked with notable hosts Jonah Reider, Tae Woo Lee, and Larry Feygin. Mike Shand, the personal chef of Beyonce and Jay-Z, reflected on how his job as an independent chef had shifted away from cooking and became more of a game of accounting and management. This wasn’t why he chose a career in the food industry.

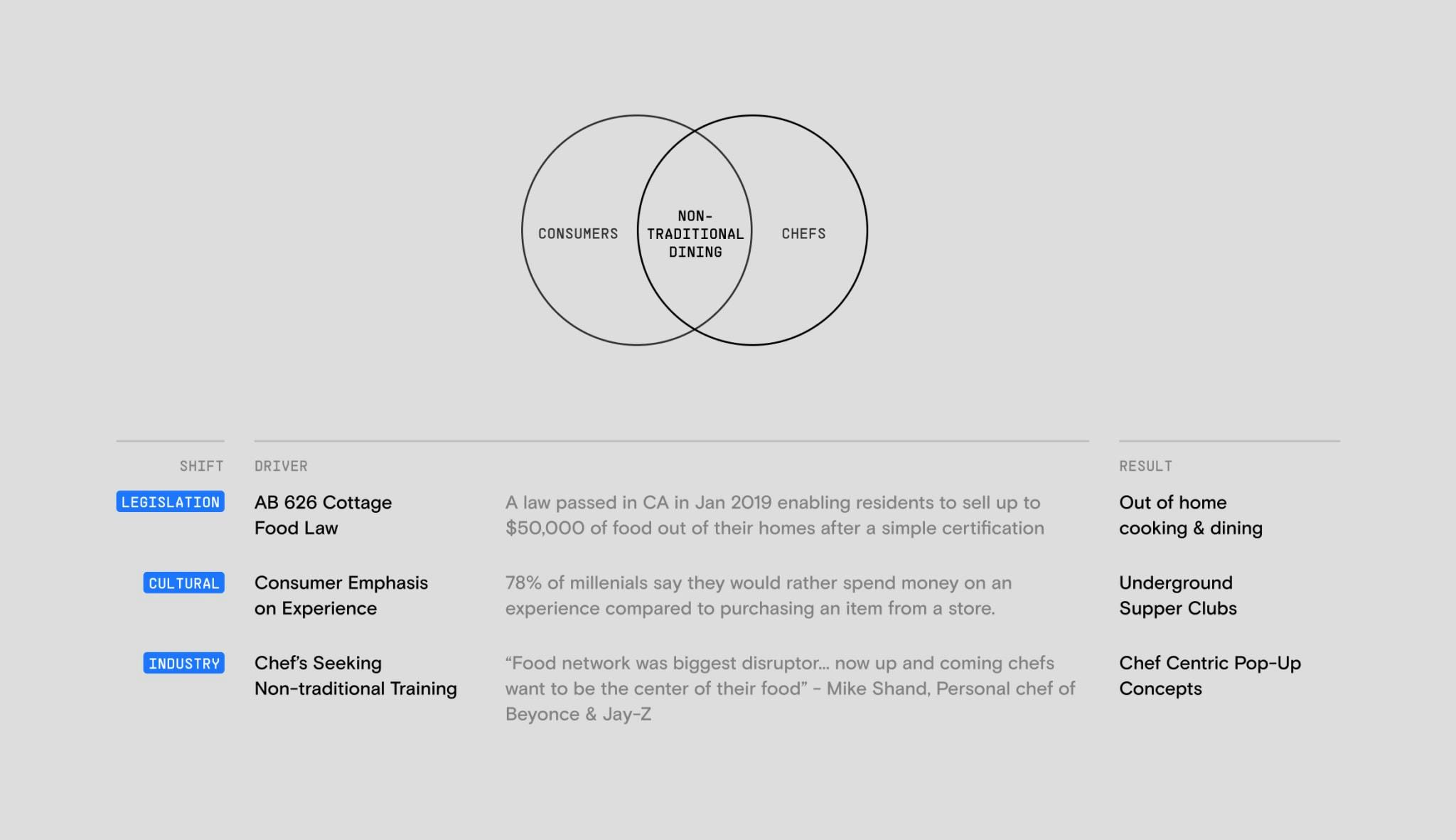

“Food Network was the biggest disruptor... now up and coming chefs want to be the center of their food” - Mike Shand.

Once we connected our first-hand interviews back to the formal research, it was clear that behavioral changes were happening not only for chefs but also for restaurants and consumers. For restaurants, start-up costs and turnover of employees made starting & running a restaurant increasingly tricky. This was a driving force behind chefs starting up dining experiences. For chefs, they were spending more time worrying about backend logistics, which took away from their passion. For consumers, those not willing to pay a premium were losing out on the social experience based dining.

Industry Transformations

The mechanization of the restaurant industry created a polarizing effect. Standardization, industrialization, and convenience consolidated lower-cost dining experiences, leaving expensive experience-based, curated, and cultural experiences as the only competitors. Low-to-mid-priced dining experiences competing on price had been pushed out. You can read compelling evidence for this trend at The Food Revolution from UBS.

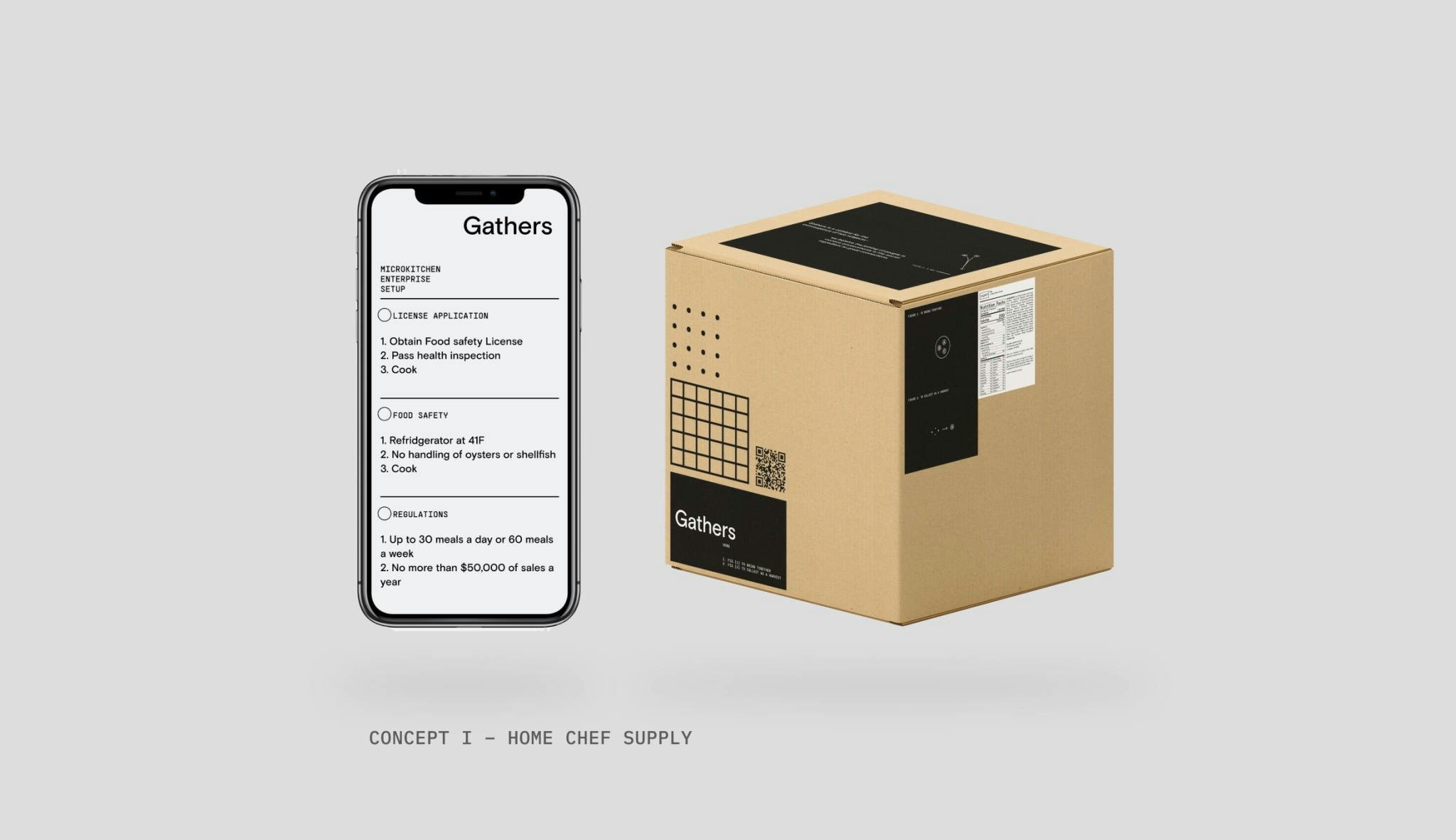

Other legislative changes at the time encouraged the growth of independently run dining experiences. In the Fall of 2018, California passed bill AB626, allowing home cooks to apply for a permit to sell food made in their home kitchen directly to the public. The bill was first intended for growing food stands and local meal-sharing operations but allowed independent cooks to formalize their operations. By doing so, residents could sell up to $50,000 out of their homes annually. Other states’ legislatures have since adopted similar “cottage food” laws.

Clayton and I found a complimentary culture shift happening during this period. Young consumers were spending discretionary income on experiences. 78% of millennials say they would rather spend money on an experience than purchasing an item from a store. This trend helped create platforms like Airbnb Experiences and grow ticketed event sales. The newfound consumer emphasis on experience encouraged the growth of small events.

The labor pressures on restaurants and the food industry further encouraged the exploration of alternative dining experiences. The career trajectory for chefs was unclear, and many didn’t see running a restaurant as a viable way to share their art. Any food experience is expensive to start and difficult to maintain.

Project Concepts

Based on the discovered opportunities, we iterated over three product concepts—each aimed to solve two or more of the above opportunities.

Gathers Home Chef Supply

We create trust and efficiency within the micro kitchen enterprise space by transparently sourcing ingredients for cooks and providing brand trust to consumers.

We would aid at-home cooks in monetizing their skill sets and provide local communities with a homegrown food experience. We offer a new opportunity for secondary income in-house rather than away from family, doing delivery services. We source ingredients weekly for home chefs, similar to services like Blue Apron and Hello Fresh. The value proposition is that each kit is made for scaling up, letting the cook make enough product to sell to their local community. With each kit, we would educate about the ingredients’ supply chain. This information became transparent to the consumer, helping them gain trust in home chefs and recent “cottage food” laws. Our approach would focus on selling everything for the experience rather than focusing on a platform ourselves.

Gathers Physical Space

A physical playground for local creators in the food space that encourages the community around the traditionally isolated hobby.

A physical location is ideal for hosting food-centric experiences, educating consumers, and providing a platform to throw events. This allows hosts to test new concepts while giving hobbyists a place to learn and share their craft. In doing so, we would build a local creator community around food. Professional restaurant networks could use the community as an opportunity to scout talent. These spaces focus on other areas of food experience outside the professional kitchen. Our physical location would act as a hub for the creative food community.

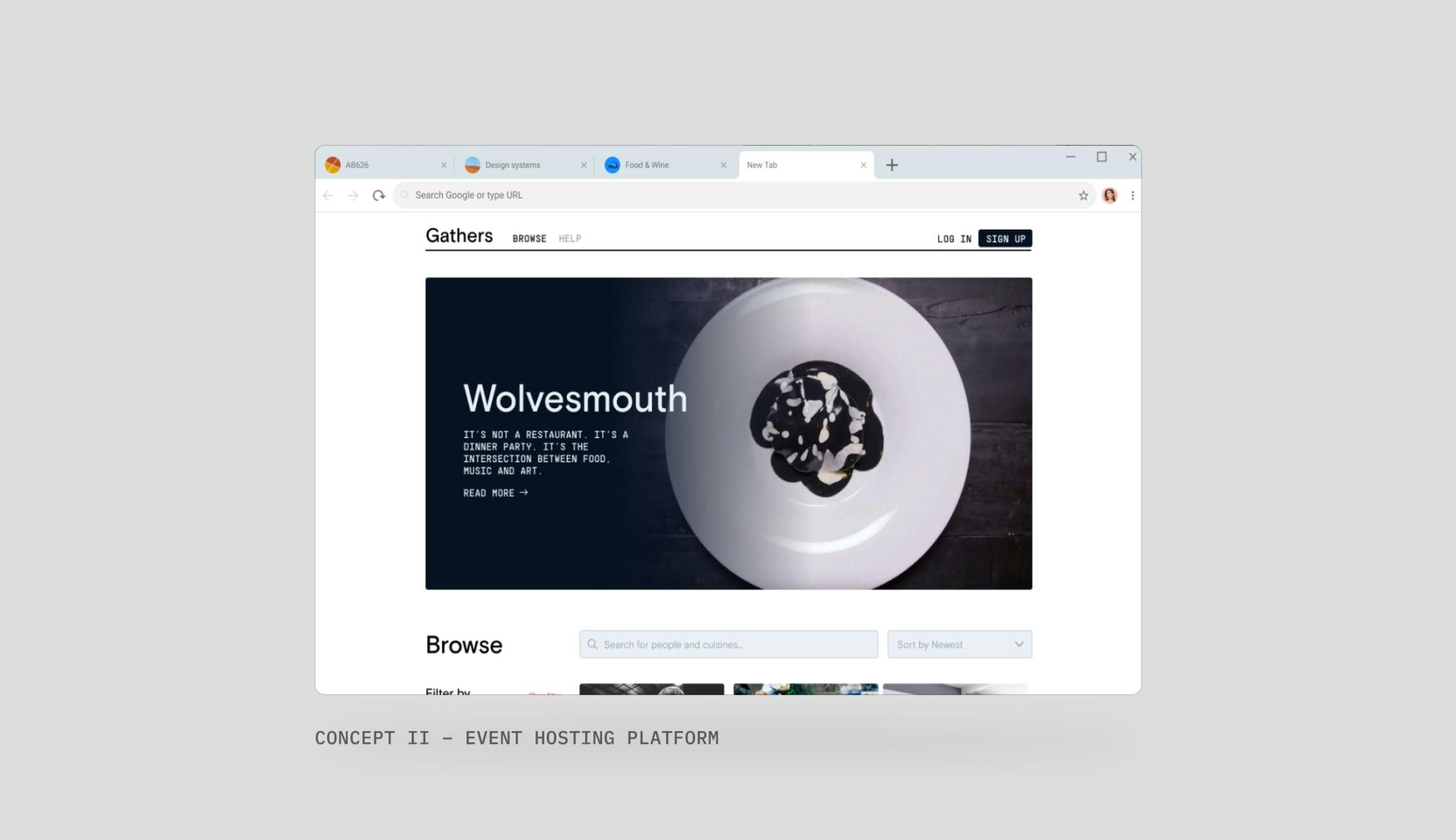

Gathers Software

By creating the connection between spaces, chefs, and consumers, we provide backend logistics to make it as easy as possible to create social experiences.

Tools like a ticketing system, guest management tools, legal advice, and web presence would help remove existing logistical burdens. If these tools prove to be effective, our repository of chef experiences could be a discovery point for consumers. Analyzing the above concepts, we found the host platform to be the most compelling to pursue within the context of our thesis requirements.

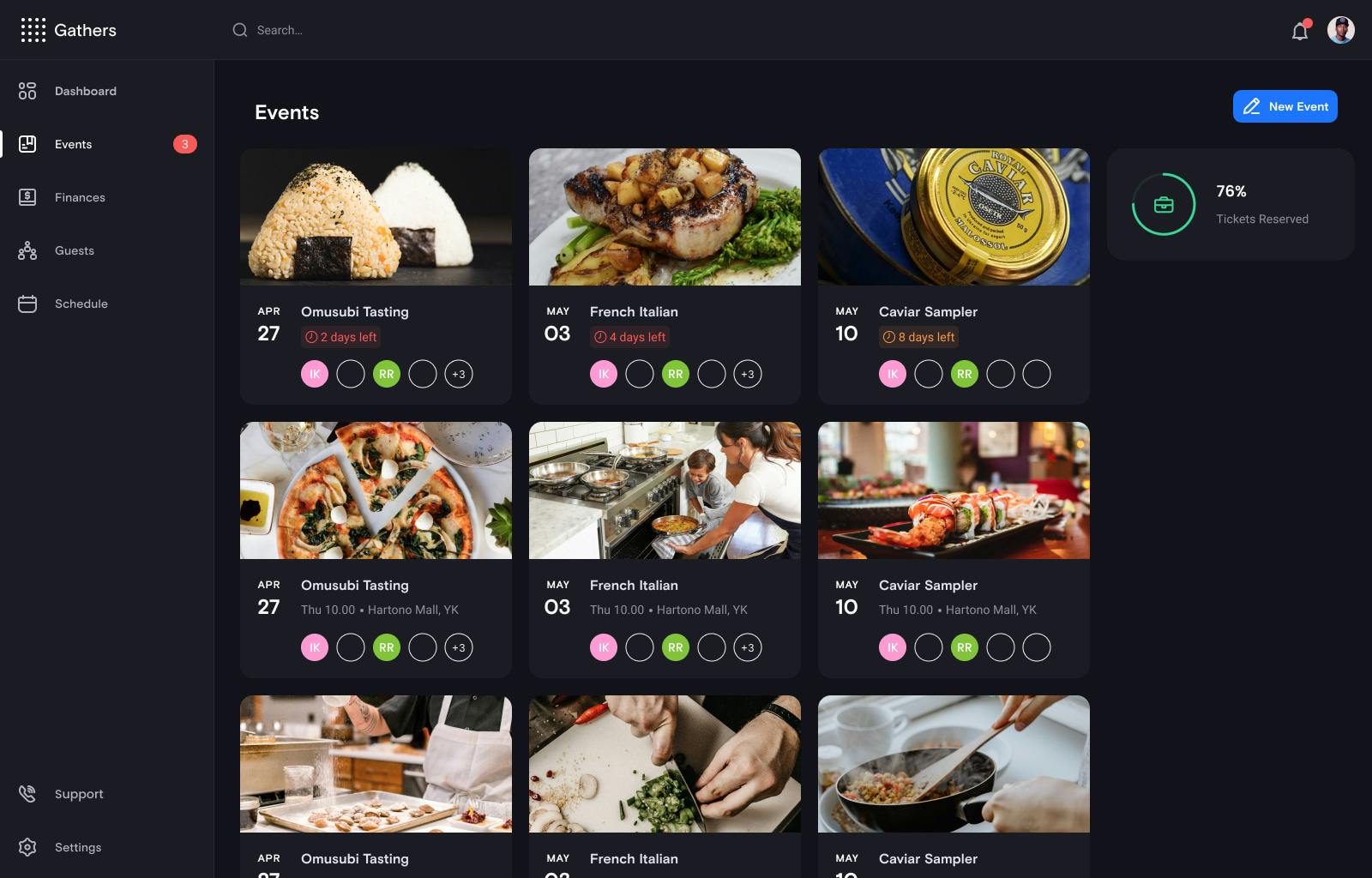

Gathers Software Platform

The hosts’ pain points and industry transformations looked like a perfect environment for innovation together.

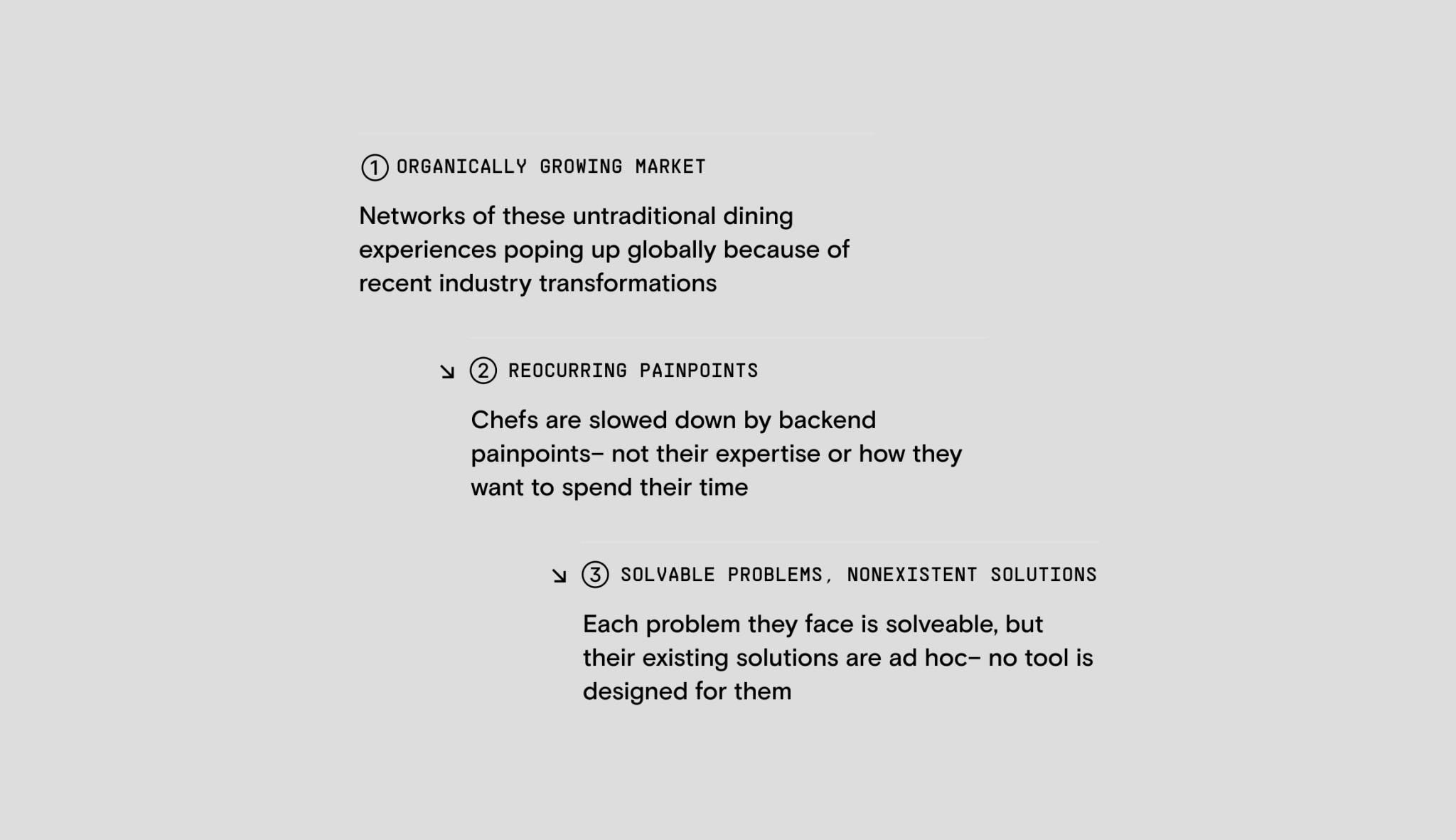

- There was an organically growing market. Networks of these untraditional dining experiences popped up globally and spread through word-of-mouth.

- Reoccurring Pain-points. Hosts were being slowed down by backend pain points– not their expertise or how they spent their time. Operations are not what inspired their independent endeavors.

- Solvable Problems; Nonexistent Solutions. Each problem they faced was solvable, but their existing solutions were ad hoc– no tool had been designed for them. We found they pieced together alternative tools to operate how they wanted. Sometimes, this was through spreadsheets, paper, and Venmo requests.

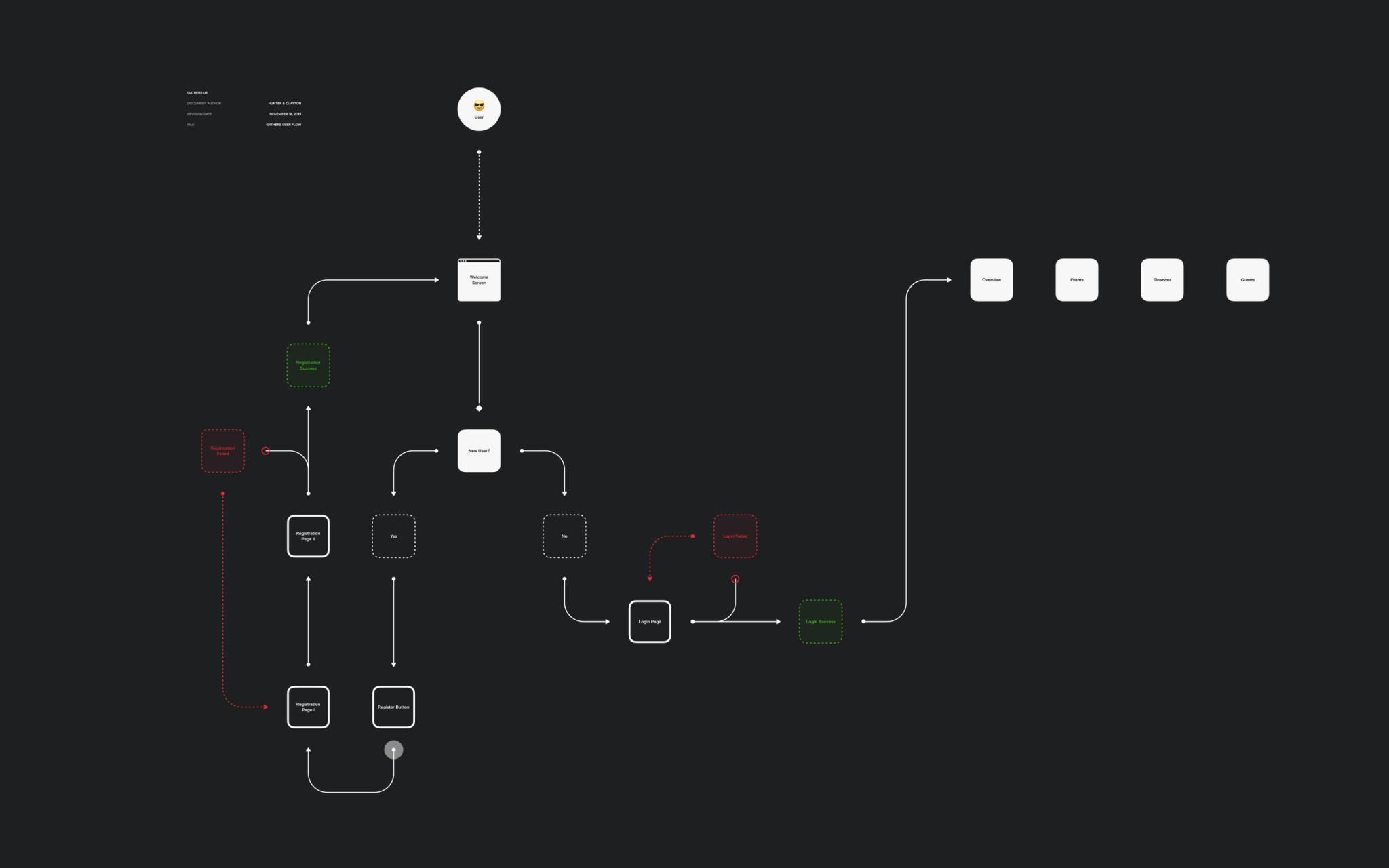

Together, these facts made the opportunity seem apparent. Gathers has found its mission: Gathers enables hosts to spend more time sharing their experiences by handling dirty operational work. The way we saw our product do this is by providing two sides to the platform.

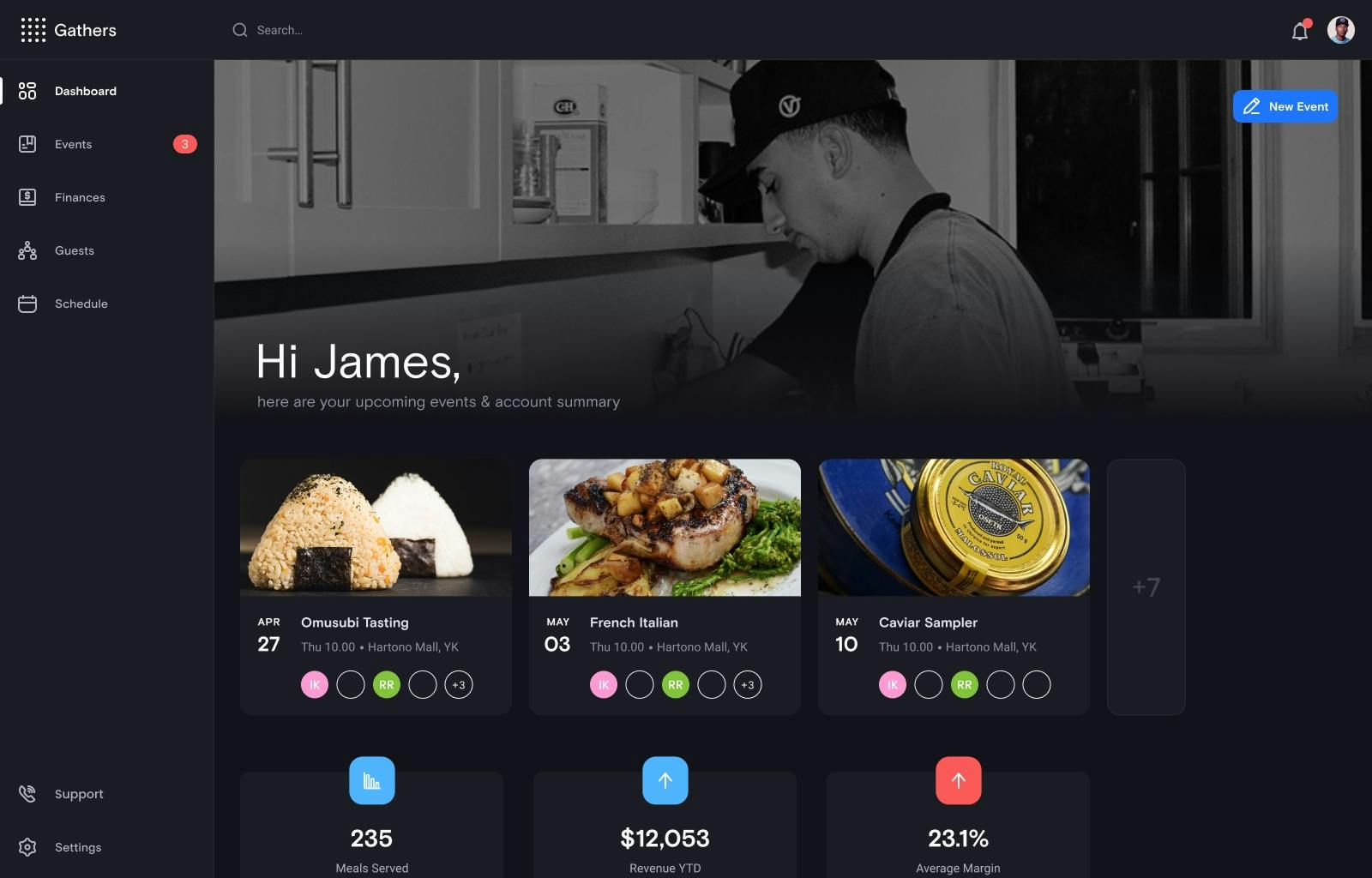

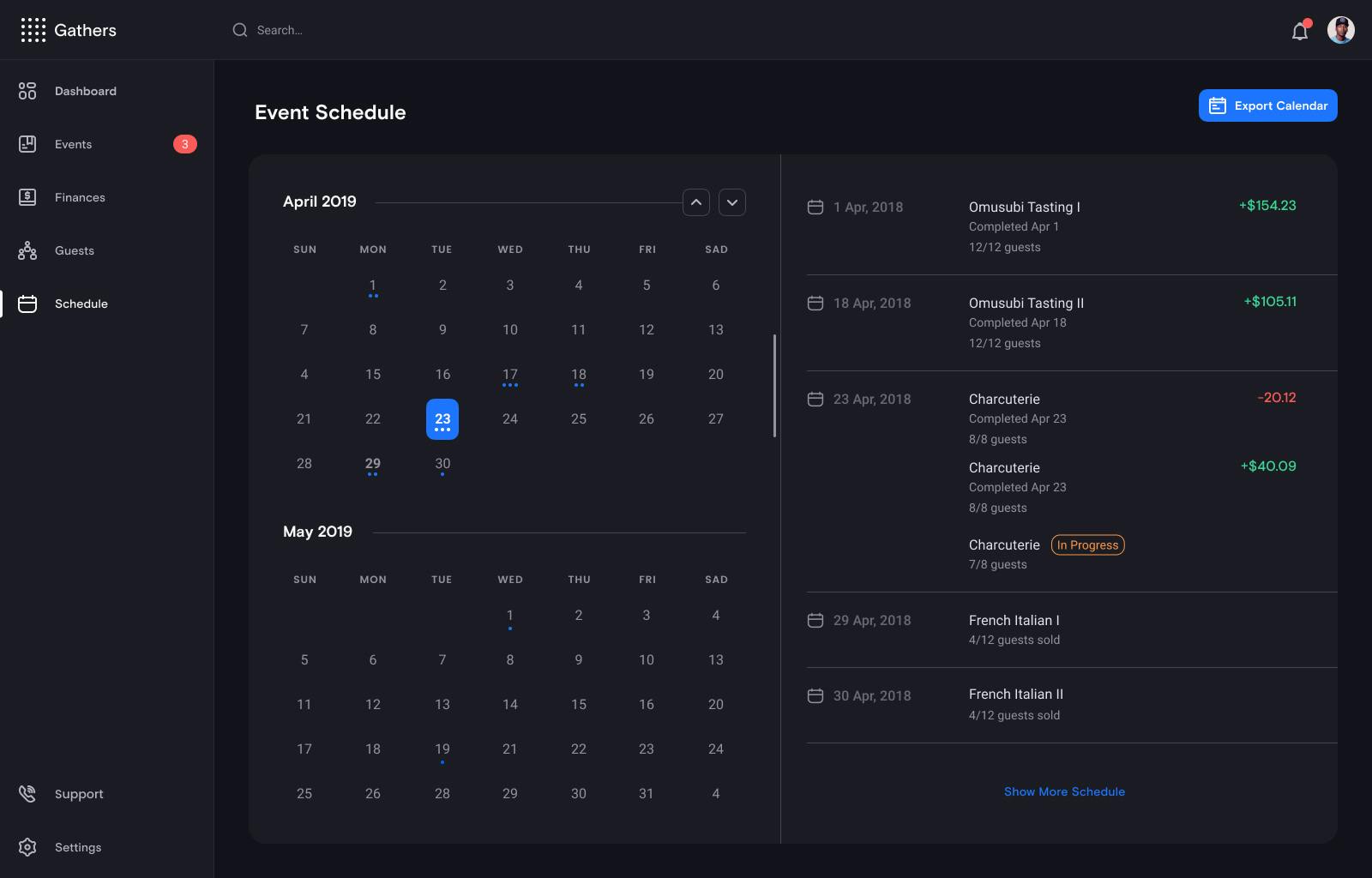

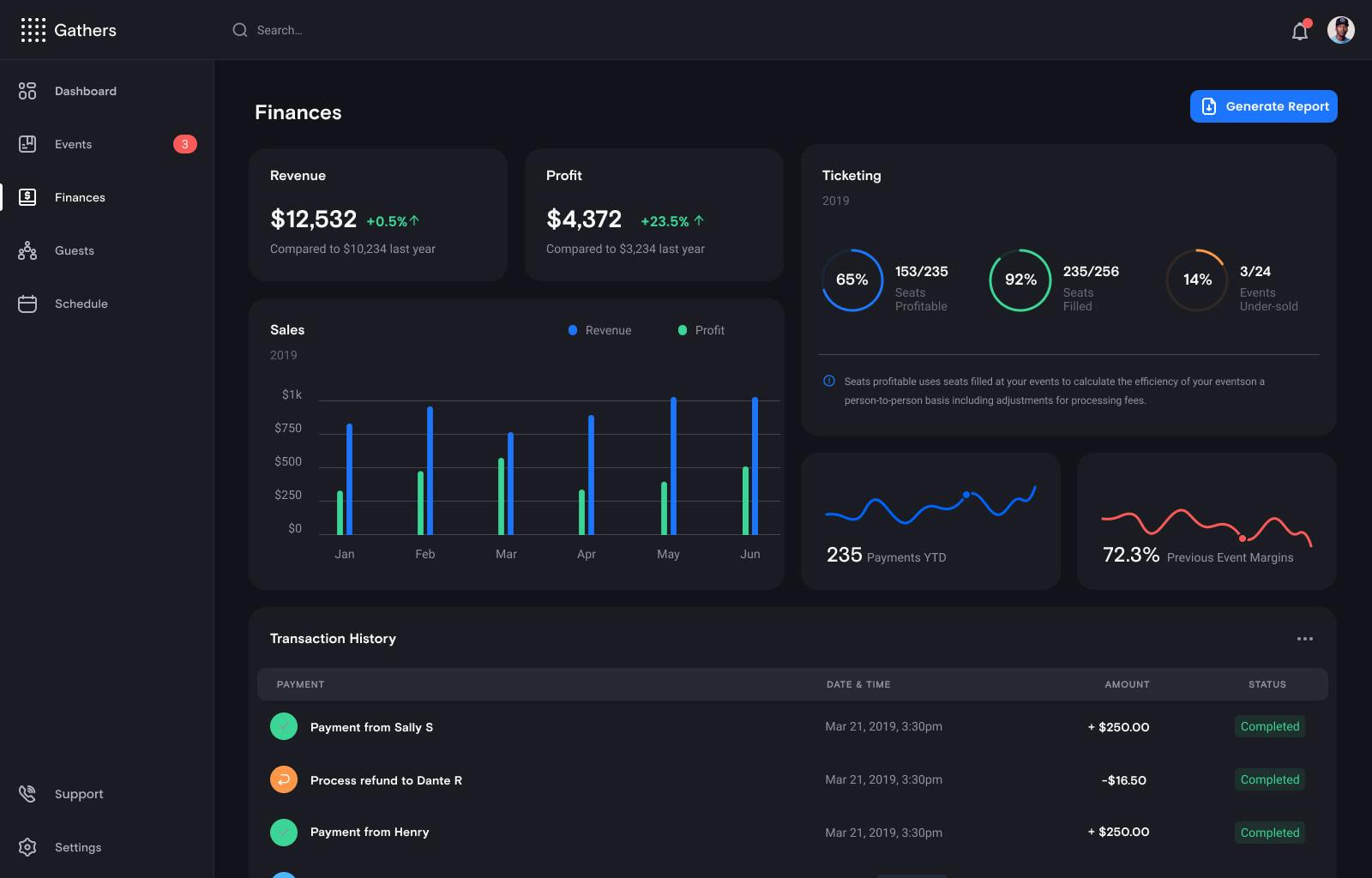

Host Backend

The backend would be the initial entry point of Gathers into the hosts’ suite of tools. It would provide structure and process where the hosts were previously finding workarounds. We would make mundane tasks repeatable and painless processes. Web-based, the tool could grow for small teams to split tasks and plan events. We also would use Plaid integrations to perform simple cost tracking for financial transparency and event pricing suggestions.

Host Value Proposition

Our management software, specific for small-scale experiences, merges backend margin analysis with front-end customer management. Gathers provides centralized oversight of experiences with easier cost tracking & better transparency. We help increase margins for experiences through budget planning, management, and customer relations.

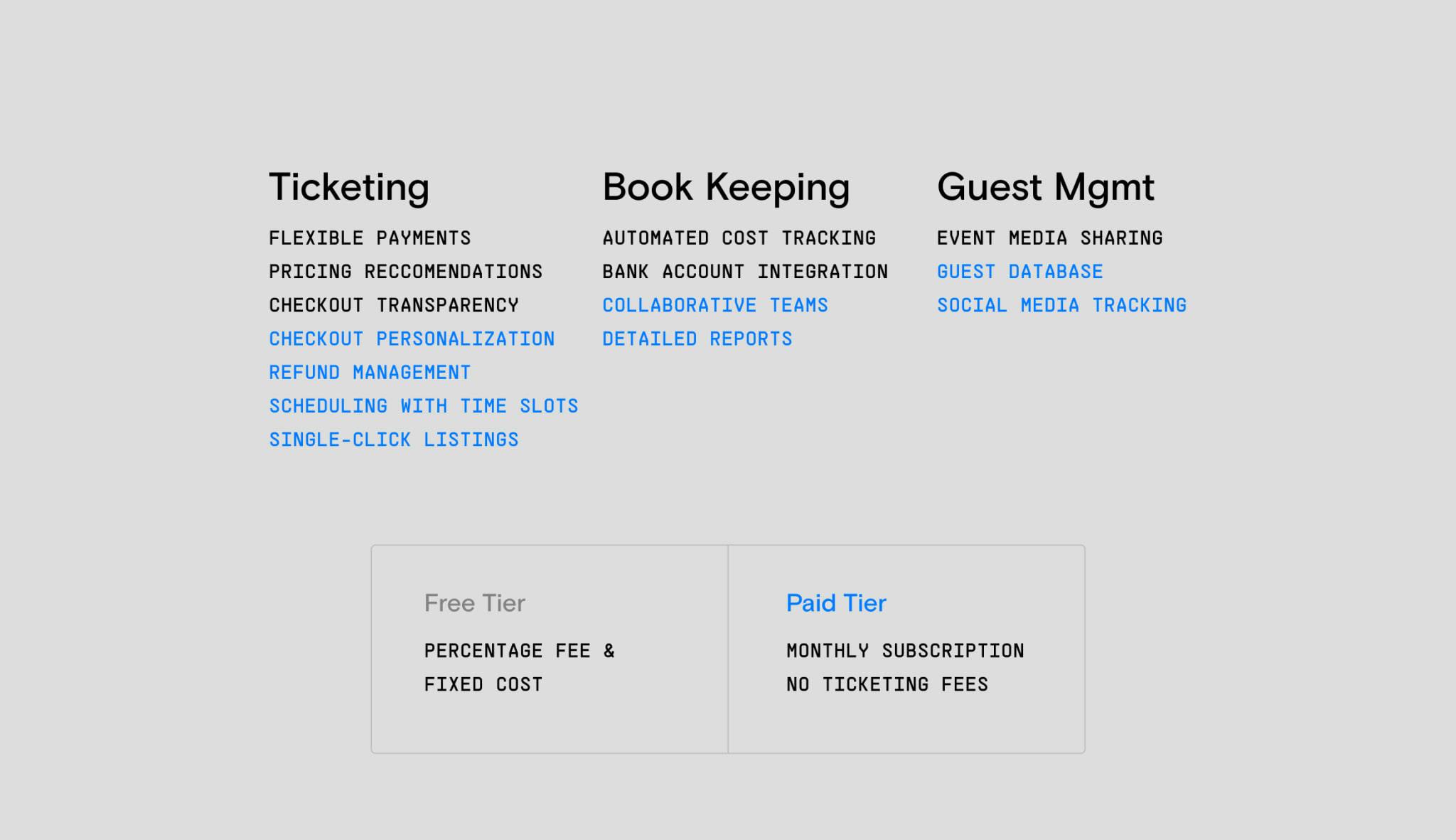

Ticketing

- Flexible payment options based on host preferences

- Pricing recommendations based on ongoing and recurring event costs

- Checkout transparency for consumers based on host preferences

- Checkout and ticketing experience personalization

- Refund management tools*

- Individual bookings and scheduling with time slots*

- Single-click listings and reoccurring event listings*

Book Keeping

Management software system specific for small-scale experiences merging backend margin analysis with front-end customer management.

- Automated and assisted cost tracking via Plaid

- Bank account integration via Plaid

- Team collaborative cost tracking and settle-up tools*

- Detailed event and period cost reporting*

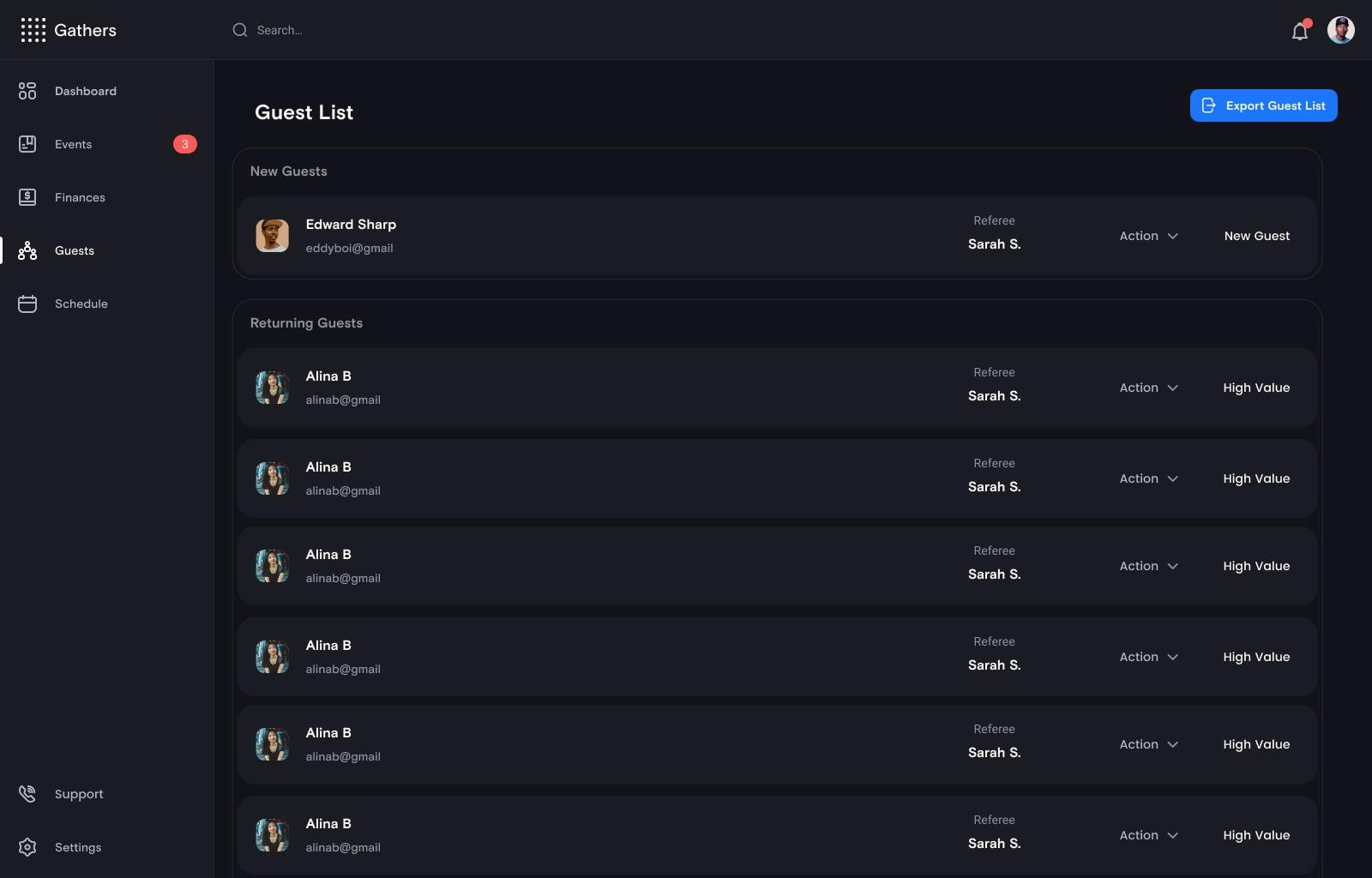

Guest Management

- Guest database and communication options

- Event media sharing

- Customized event pages for loyalty initiatives

- Social media link tracking and source analytics*

Monetization Strategy

Along with the base feature set for ticketing, finances, and CRM, this operational platform lends itself well to a freemium model.

Free Tier: The free tier of Gathers would charge a fixed processing fee and a percentage fee for every ticket sold. We would provide access to all the non-italic features above for free tier hosts.

Paid Tier: The paid tier of Gathers would charge a monthly subscription with no percentage fee on ticket sales. For hosts willing to upgrade to the paid tier, we would provide access to the additional tools above italicized.

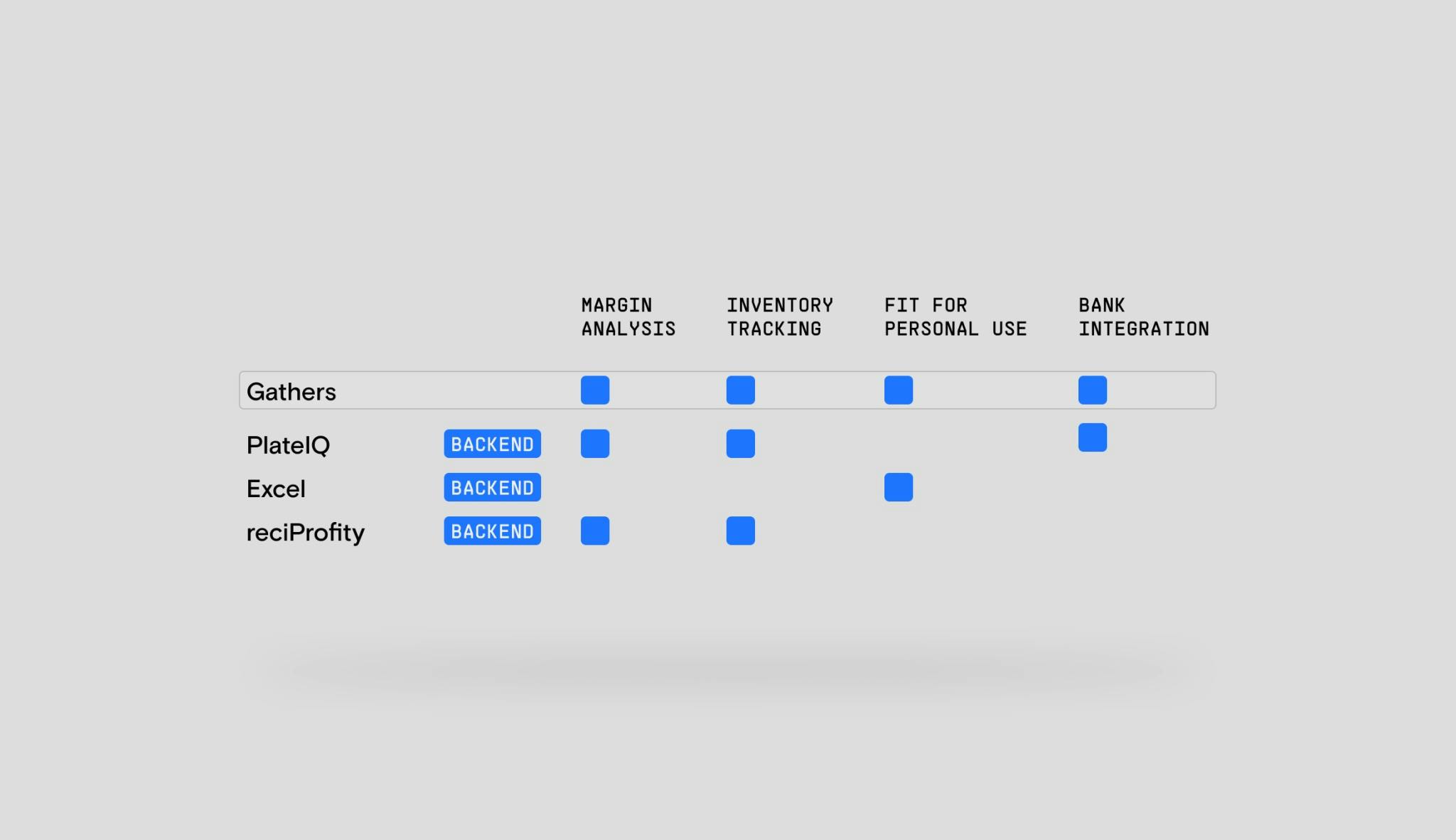

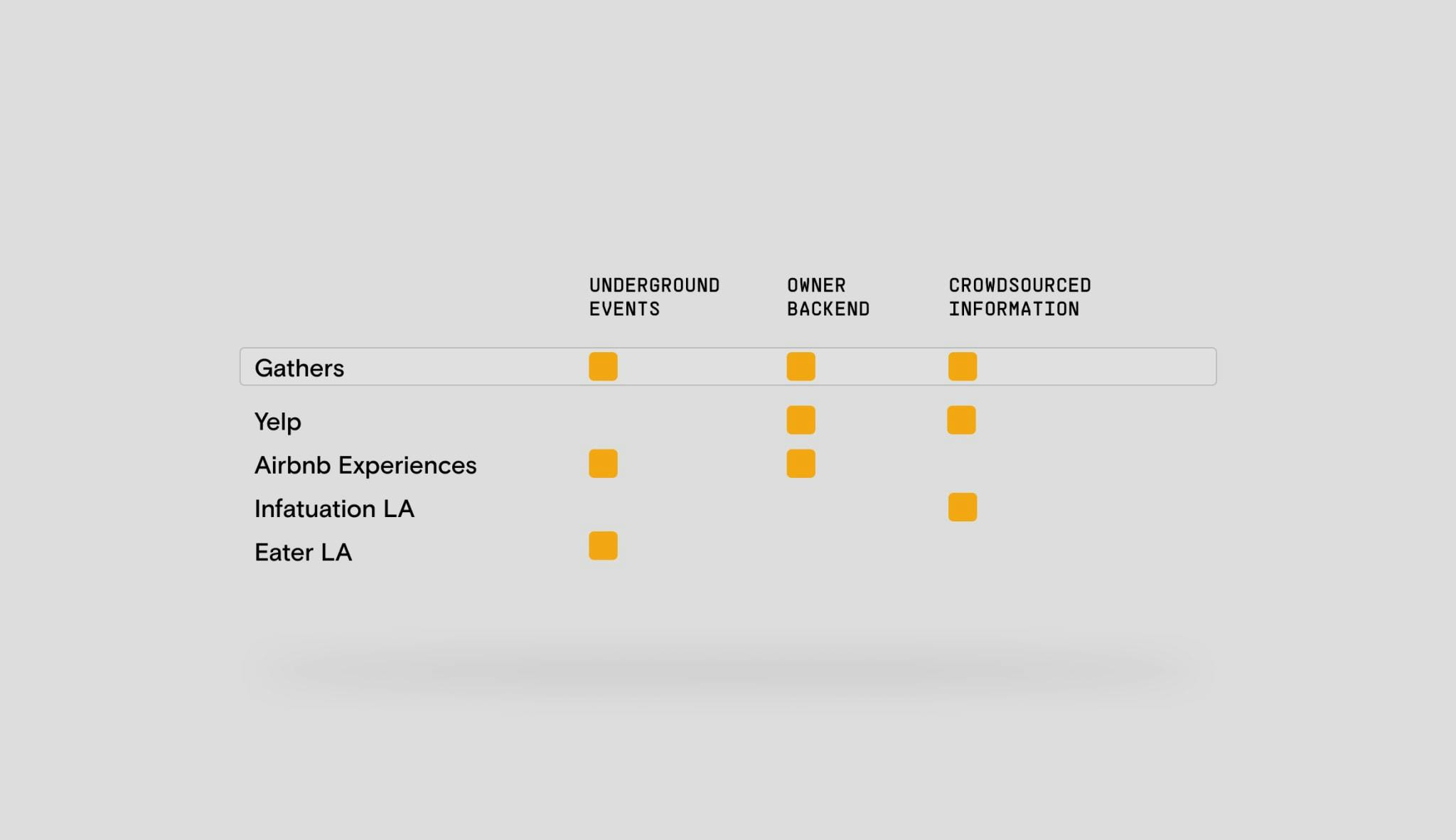

Competitive Positioning

By design, Gathers was the only tool that simplified both the backend and ticketing of experiences.

Consumer Frontend

After gaining traction among event hosts, we would use our network as a public repository of ongoing events. Email lists and simple signups would help the hosts manage customer relations and offer loyalty initiatives. Growing this consumer-facing side of our platform would allow us to further educate about local, small events.

Discovery

- Current events

- Chef spotlights

- Availability alerts

Education

- Legitimize small operations

- Incentivize individuals to become hosts

- Link to partner sites

Community

- Network recommendations

Competitive Positioning

Naturally, Gathers fits in as a desirable consumer platform for small event discovery.

COVID Interruptions

We were on track to develop a working MVP and test with various chefs and events in March and April of 2020; however, COVID-19 and stay-at-home restrictions threw a wrench in our plans. So we decided to pivot to see how Gathers can help chefs facilitate digital food experiences that still adhere to COVID-19 restrictions. We started by seeing the short-term changes in our communities. After doing so, we tried to apply game theory practices to understand the possible long-term implications of COVID-19 better.

Observed Cultural & Industry Responses

- Increased home cooking

- Reduced dining experiences

- Zoom happy hours and shared teleconference meals

- Increased delivery and takeout

Predicted Cultural & Industry Responses

- More significant experiences as there were fewer and far between

- High number of restaurant closures

- Increased staffing pressures

- Legislative changes around food handling

- Restaurants diversify revenue streams

Virtual Cooking Experience

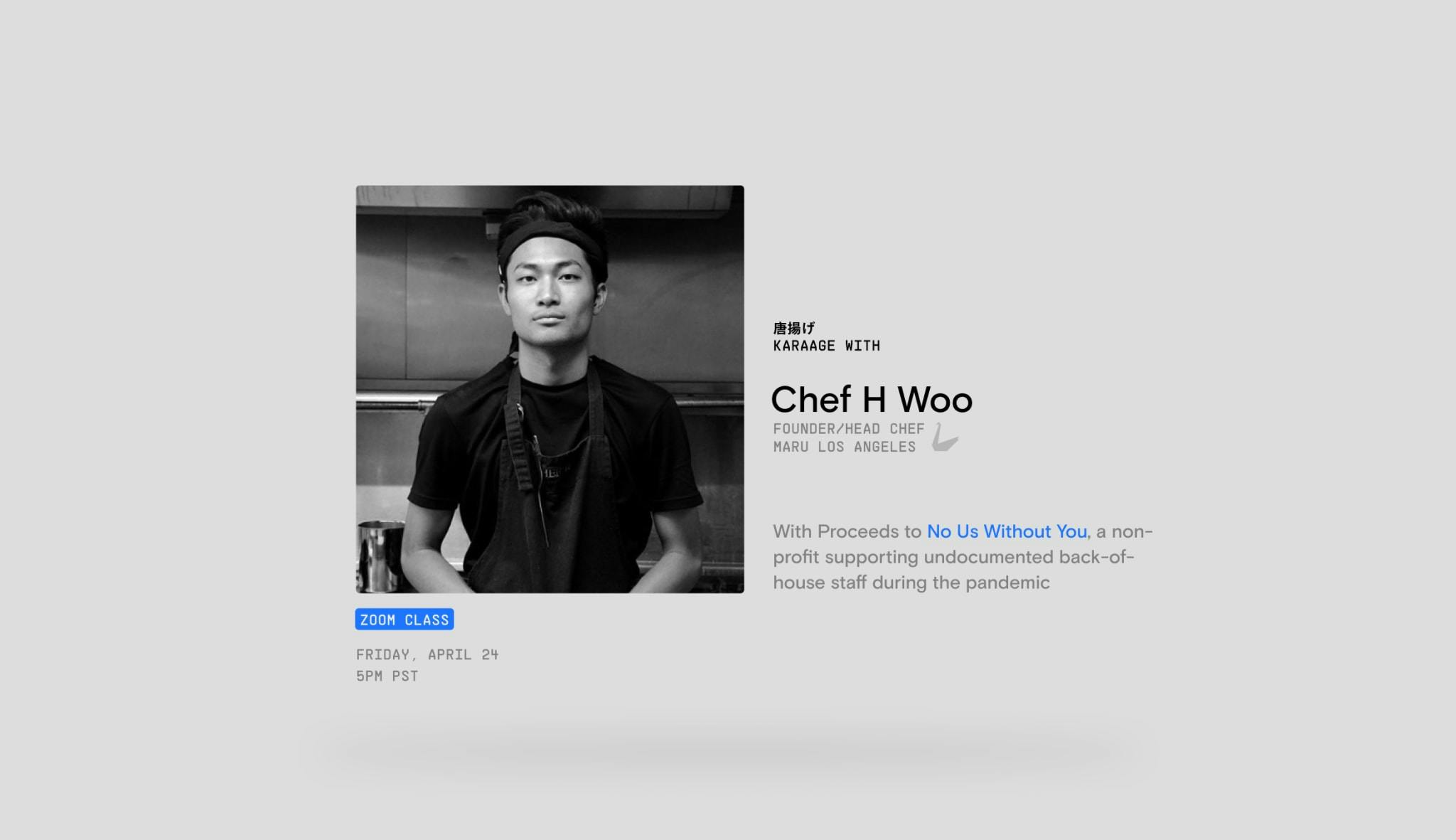

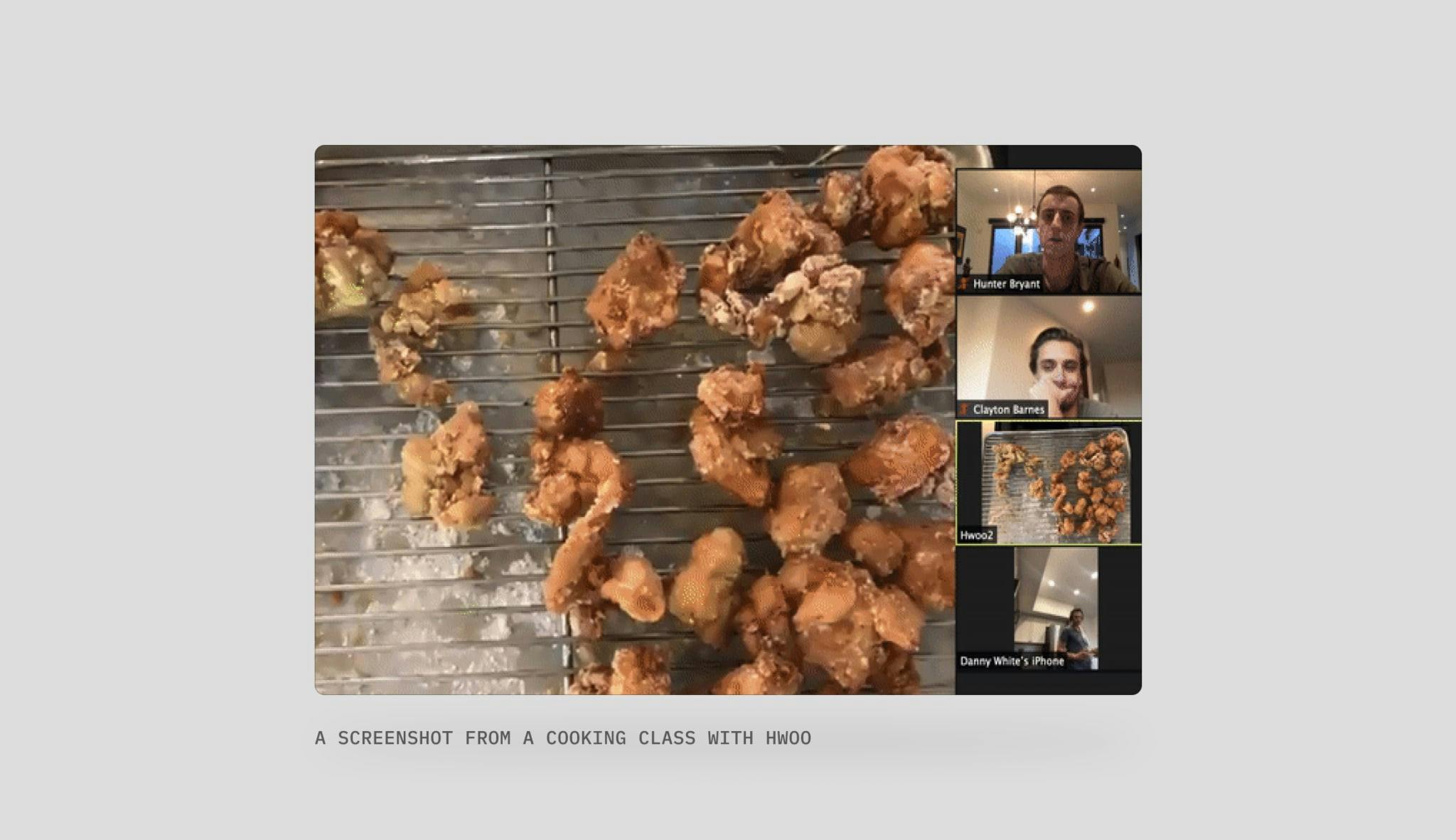

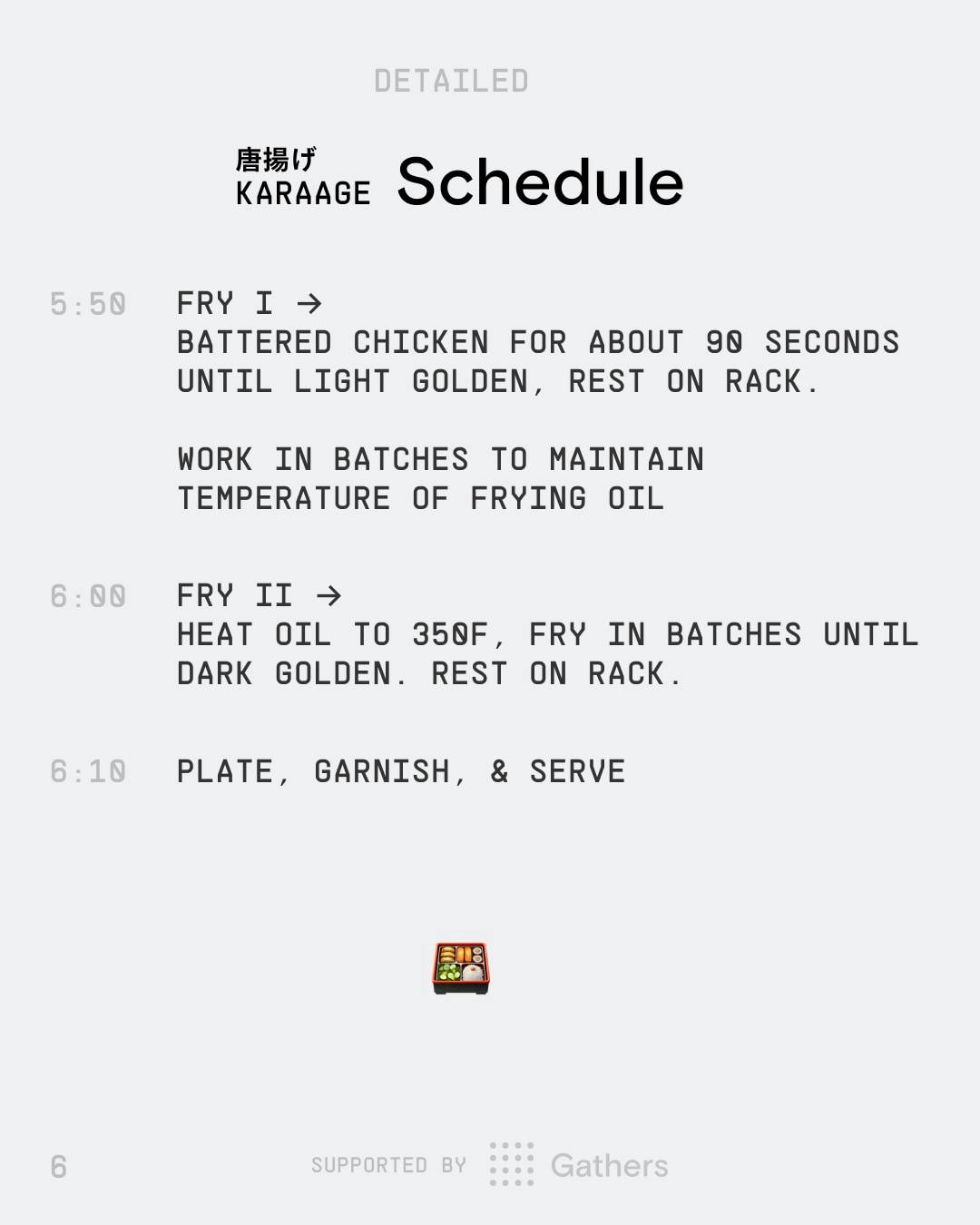

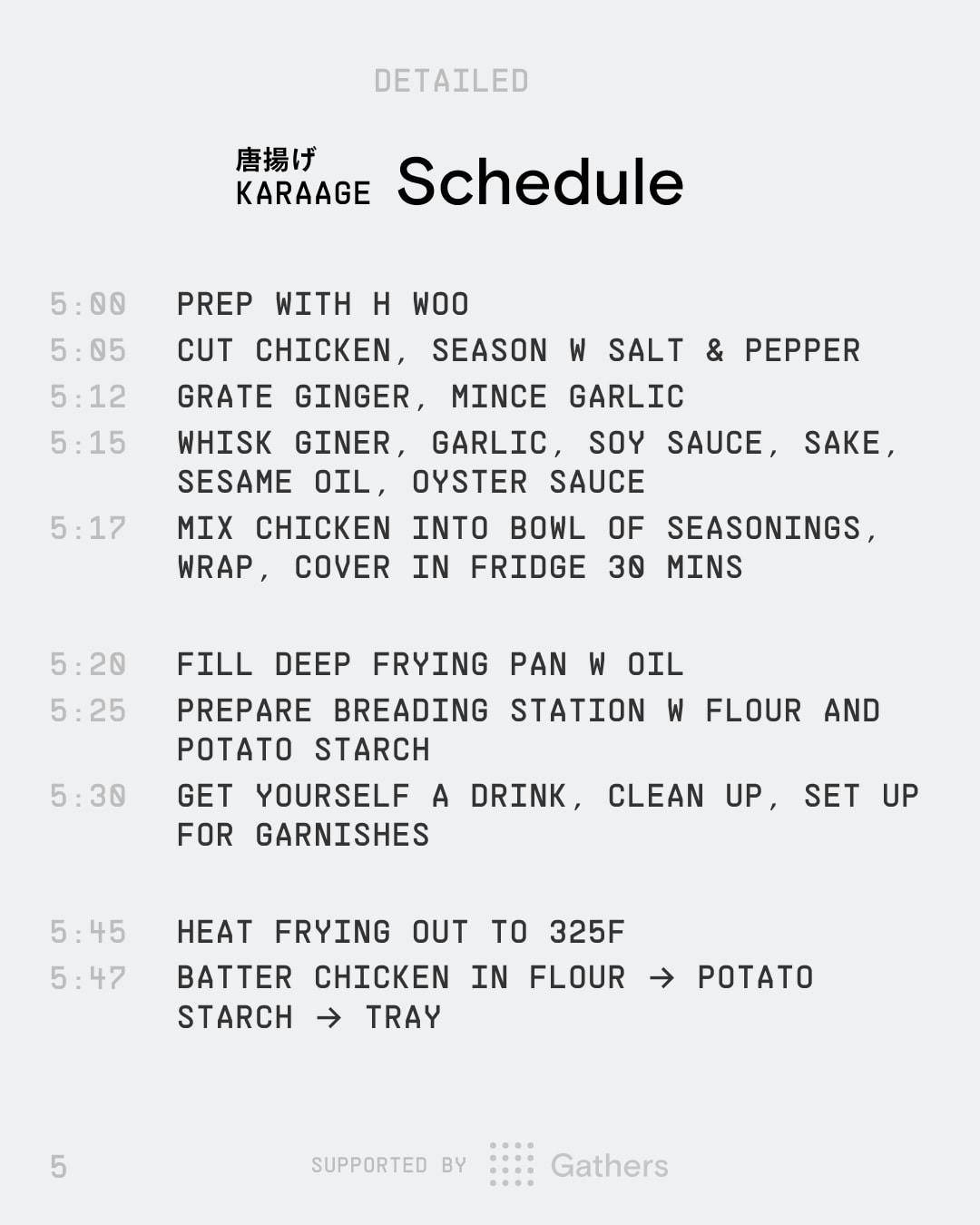

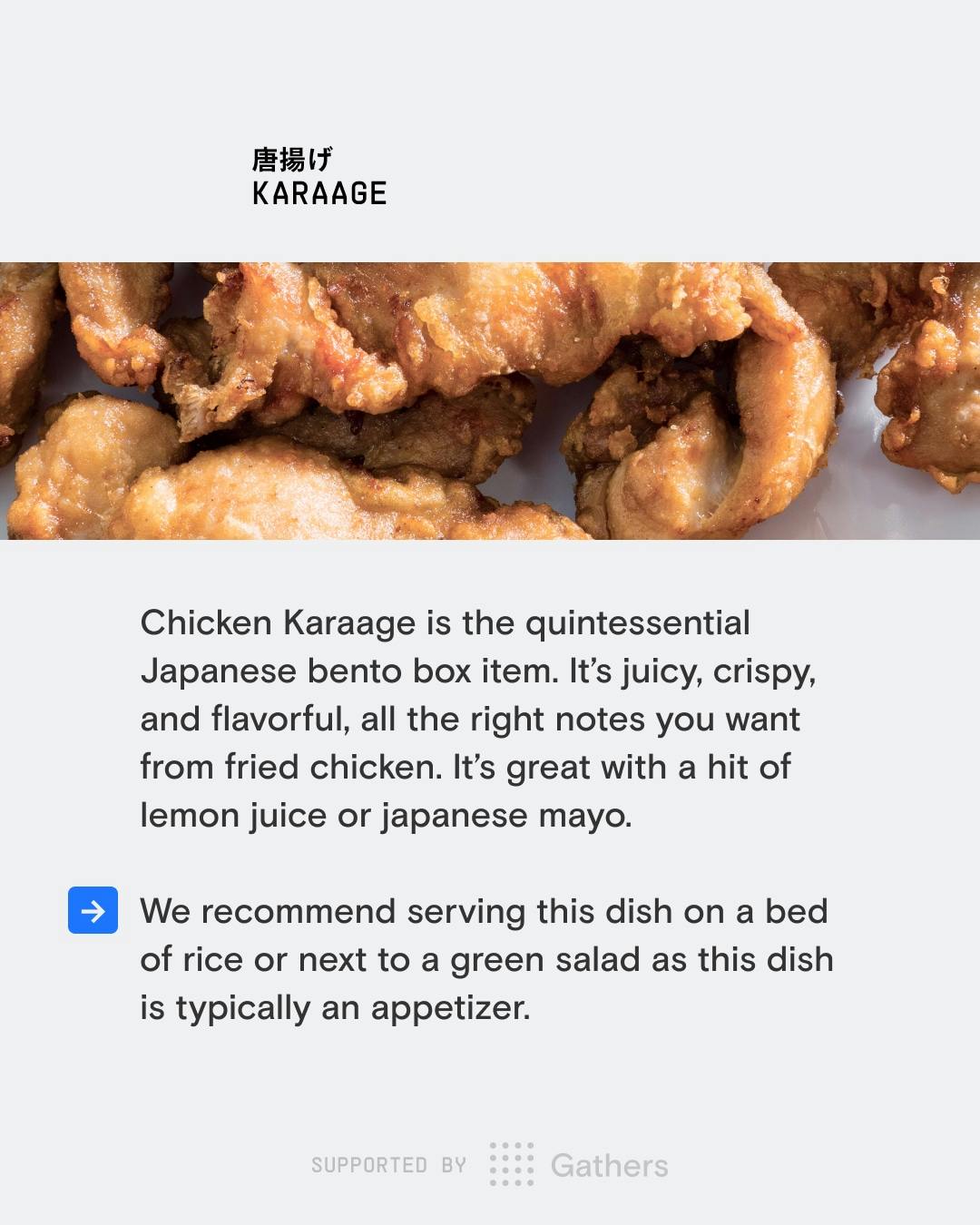

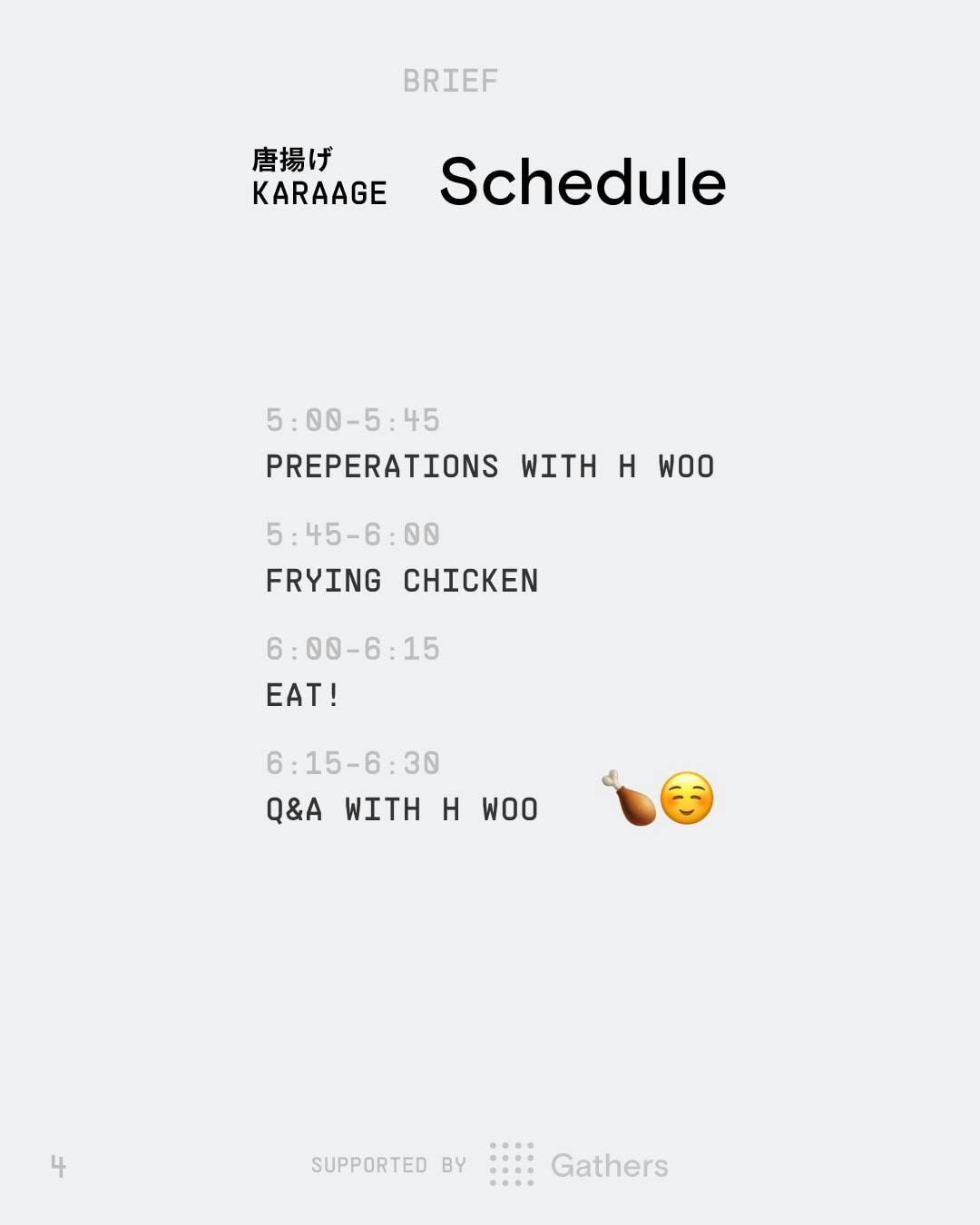

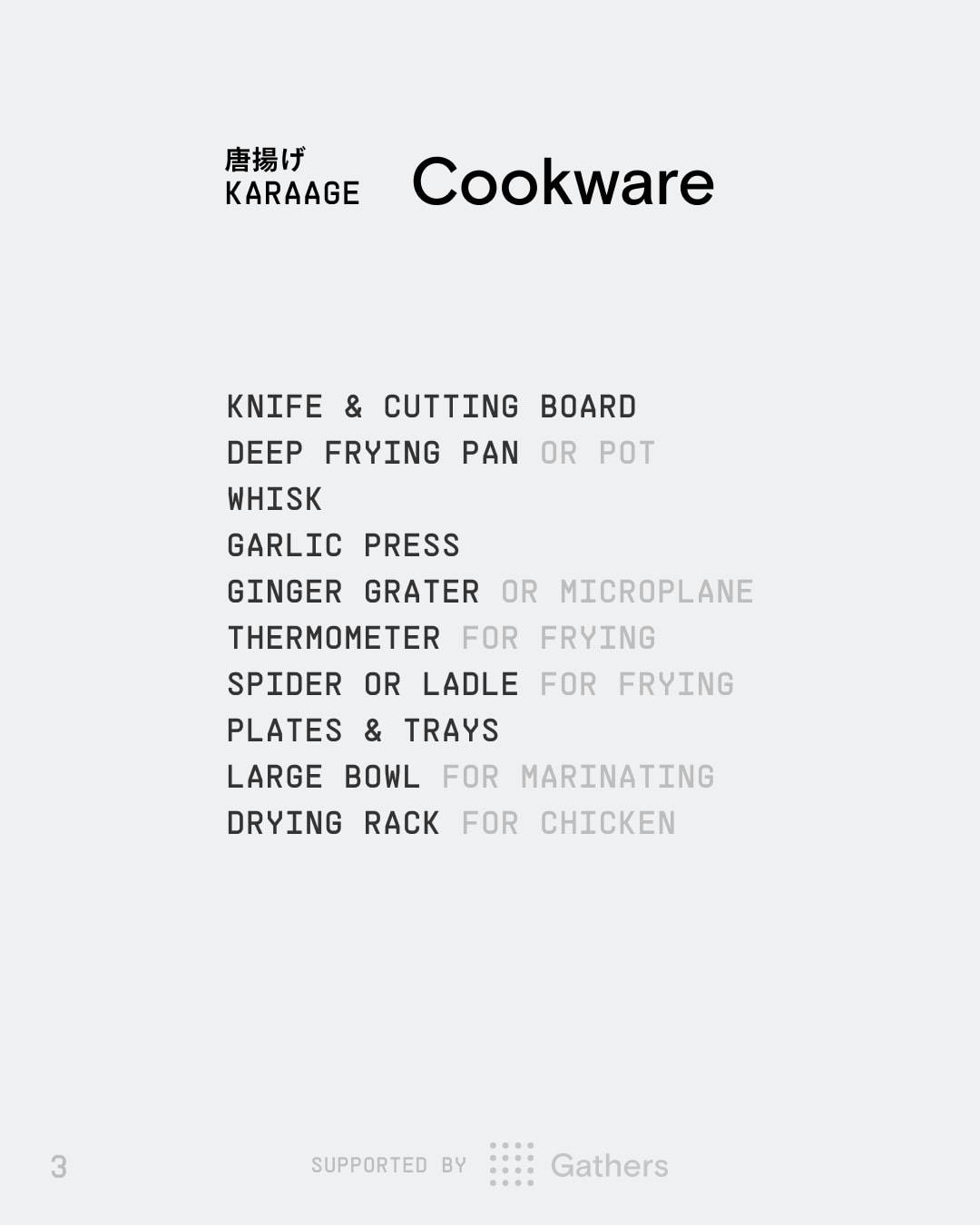

Clayton and I began working alongside Chef H Woo to demonstrate virtual experiences we could package for other hosts. Our first event was an at-home Karaage cooking class, with proceeds going to No Us Without You, a non-profit supporting undocumented back-of-house staff during the pandemic. To create the event, we built a prototype of our ticketing platform for attendees. We supported H Woo with the release of event assets and personal branding. On the event day, Clayton and I produced the event, including camera setup, live production monitoring, and distribution of event assets. Our supporting role in this event was an early example of highly-produced remote experiences during the pandemic.

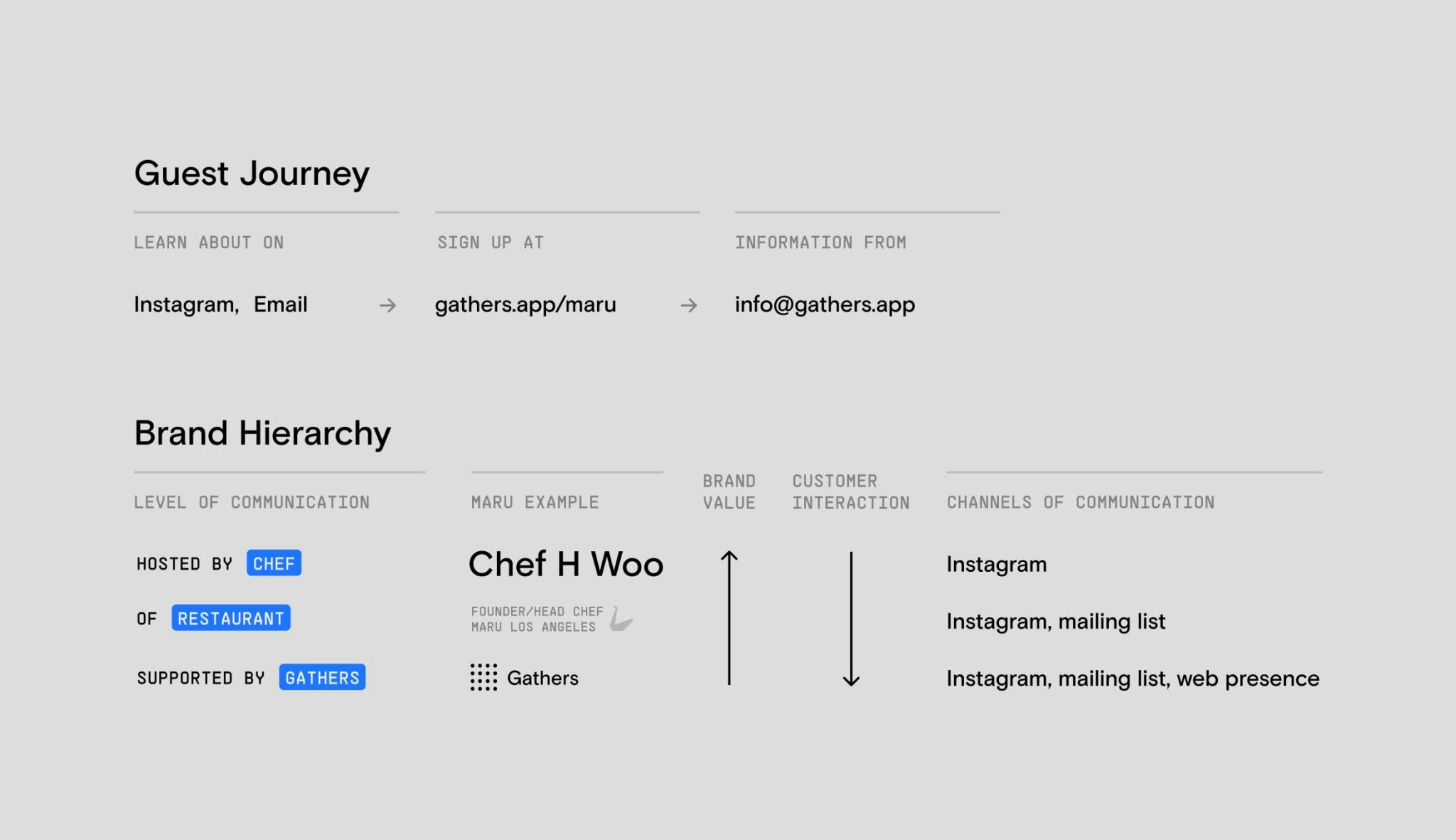

Communication Strategy

This first remote experience helped inform us of the challenges of remote hospitality. We found that it could be difficult to convey individual hosts’ brands with Gathers and what role we played. As we aimed to support chefs, it made sense to make the event’s marketing focused on the individuals. Our platform leveraged these individual brands as a catalyst for networking between guests and experience discovery. Our follow-up iterations on the project showed us that we had to tailor our presence to the hosts’ existing communication channels. It was also helpful to create artificial scarcity for event signups to maintain intimacy previously found at the in-person experiences.

Industry Changes

The first few months of COVID-19 in the U.S. sped up some of our predicted industry transformations. In some cases, the restaurant industry moved quicker than we thought; in others, growth stunted. While most restaurants were on the losing end of the crisis, the unique circumstances gave way to creativity and disruption. As the industry scrambled to save itself, new forms of dining and food experiences adapted to the new landscape.

Parting Thoughts

Working on this project was a great experience to teach us how to identify problems that could develop into market-fit products. Our most significant regret, looking back, was how we waited to start development until we had “enough” research. There will never be a defined “enough,” and quickly iterating would have validated our product sooner. Implementing our concept and throwing events with H Woo taught more than our research alone could. The big takeaway? Move quick. Gathers began as a means to understand how people interact with food and the forms of experience that arise from those interactions. Our knowledge has helped us know where the industry came from, where it is headed, and how we can help people connect through uncertainty.