In Search of Birch

There’s a classic interview, something from the late 90’s/ early 2000’s, where Jeff Bezos is asked about his decision to leave his job and start Amazon. He begins by explaining his framework of living, in which every decision is made to “minimize regret”. I’ve always liked the idea, but Bezos, man, get your priorities straight. Try skiing. It’s better for the soul.

Still, I think there’s truth in the idea. Sometimes I find myself thinking back to the quote when feeling lost about life’s decisions. In the past several years, I’ve had the privilege to try my hand at living on both coasts– in NY & LA. While I stand by these choices, I’ve always known that life in the mountains would someday draw me back in. I’m not sure if it’s time to come home, yet, but the withdrawal symptoms of mountain abstinence have been getting stronger.

I’ve been missing time spent with friends who share some underlying understanding of how life should be lived. Through play, we remain kids. A small group of us have started to find ourselves traveling to climb and ski together once a year. A convenient byproduct of these trips is that they return us to a shared reality known to mountain people.

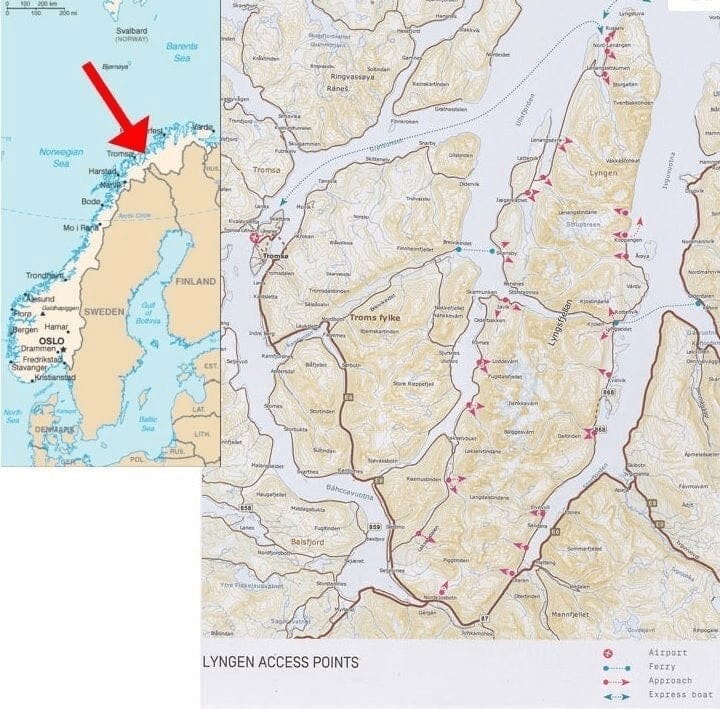

The following photography and accompanying text contains snippets from my account of this year’s big annual trip searching for lines in the Lyngen Alps.

Intro

Again, I’m late to the game. Three days into the trip and I finally start to journal. I thought I’d be good this time and methodologically take notes. Looking back on past trips, I realize I forget about the little moments traveling. This could be items like convenience stores snacks, interactions like the negotiations with car rental agents, or arguments over grocery strategies. It makes sense that these aren’t the memories etched into our brains’ long term storage, but these moments lay the foundation for our nostalgia. The moments in-between make up the essence of our memories. With the knowledge that this trip is the grand finale for the year (my internal record starts and stops with spring missions), I have to keep note. Getting blindly lost in the moment might lead to memories being lost forever if not for note taking. I’m looking forward to the day that I’m old and stumble across this document: Norge2023.txt.

Day 1– Tromsø

Not too long ago, I thought I knew all the major ranges for good skiing . Growing up in a town of ski bums, I was well aware of the usual Alps, Rockies, Alaskas, and Hokkaidos. I was suffering from a severe case of Dunning-Krueger effect. The Lyngen Alps wormed their way into my head after a side comment from a friend, relaying a statement from another friend. I have a lot of respect and trust for this individual, so when they mentioned Lyngen was on their bucket list, I was intrigued. Two years later, I’m returning to Lyngen for the second time.

By the time I land in Tromsø, I’ve had an Icy Hot on my back for the past 10 hours. I wish I could tell you the pain resulted from overtraining or a wild crash. No. My back gave out after a few long days working out of my knockoff fiberglass Eames chair. There is nothing more concerning than an injury days before a trip planned years in advance. Fortunately, the jet lag gods were on my side this day. I manage to step off the plane feeling good. Cole rings my line to tell me he’s waiting in the lot. I’m the last to arrive.

At the hotel, the group is in ski gear. Waiting for me. Without notice. I quickly transition from travel to ski mode in the hostel. For the layman this would be a time consuming task. I am no layman. I am Hunter, master of adventure packing. A few minutes later and we are whipping in the rental Skoda.

We fit 45 minutes of house music in the drive. Not my daily mix, but I can deal. I had no idea where we were going, but the others seemed to have a plan. We show up in the zone. The first parking lot: full. The second: full. We found ourselves parking a solid mile from the intended trailhead. Clearly ski mo is a Norwegian pastime. From the lot, the mountain we aimed to ski appears massive. It was big, alright, but our eyes had played tricks on us. There is a strange visual phenomena out here. It’s a type of optical illusion where the lack of foliage this far North makes everything seem bigger. There are no trees to give sense of scale. A mile ski later, our first switchbacks start.

Views from the lot. We briefly met a group from France. This zone seems to be a popular choice for it’s proximity to the city.

100 kick turns in and we crest the summit. On the up we were passed by 3 groups with no downhill skills, 2 ski mo racers in tights, and 1 guy rocking shorts and a t-shirt. Legend. From the top you can see far North-East towards Tromsø. The tips of Lyngen peaks in the back. We will be there soon. We transition into downhill mode and traverse the ridge. With six skiers and several couloirs, we split into groups of 2. Hunter Hill and myself got into the first Coulie. We make quick work of the classic spring corn / slush. Perfect conditions for our warm up day. At the bottom we radio the others and watch their lines from below. Then, a mad dash to the car. With no foliage to block our way, it became a game of red-lining on unpredictable snow.

We return to Tromsø. We go out. We end up spending too much on highly-taxed Norwegian pilsners at a strange local club (if you dare to call it a club). They have free mini golf inside of the club. Americans: take note. Back at the hostel, we pass out.

Day 2– The Canyon

My feet are in pain. I can feel hot spots coming in, so I avoid skiing. Last night I stayed up doing NSA-level recon on line choices for the day. There is a certain notorious local pro who posted a GoPro clip a month ago. He made quick work of the line, describing it as a hidden treasure. There is no tagged location, but we had context clues from the mountains in the background. Using dead reckoning skills and a sun triangulation app called PhotoPills, we were able to deduce the line. For fear of local-retaliation I will keep the pro’s identity and line hidden. If you want it, ring my line. The couloir in question is about an hour drive South of the city. Binoculars in hand, we headed out.

From the base, it may go. We link the bino’s to my tripod and analyze. The boys skiing want to give it a shot. While they approach, I relax in our hatchback e-Jag and bump my favorite Norwegian rap– Tøyen Holding. He’s repped by Mutual Intentions, a group of Scandinavian artists that put out clean music. While rhythmic gibberish pierces the air, I watch the sun drift horizontal to the horizon. The wind picks up. The clouds grow.

Hours later I get a call from them on their radio. While I’ve been relaxing, they’ve been getting socked into their canyon-like couloir. They were ready to turn around now, but they were concerned about descending through the off-axis crux in low visibility. One by one they appear below the cloud line. Relief for them, spectacle for me. They party ski through the rest of the line as I watch on tripod. I’m jealous.

We drive back. That night we tasted whale & reindeer. Neither bad, neither great.

Day 3– Travel

I’m considering this a down day. The main mission of the day is to stock up on food for the weeks ahead in the mountains. Once we leave Tromsø, there are limited services on the Lyngen peninsula.

First , breakfast at our tiny hotel. I visit the boot fitter to get work done. Coffee. We hit the market and grab a massive salmon fillet. Twice the quality of Whole Foods for half the price.

We go to Tromsø Badet– the most beautiful goddamn rec center I’ve ever been to. It has a world class climbing gym combined and unrestricted access to high dives and saunas. My dream. We watch Stosh, Henry, and Hunter Lee compete for the most dangerous stunts I’ve seen. Someday I’ll do the high dive belly flop. Not today. After smacking the water several times, we leave with mild headaches. Once in the cars, we drive off towards our first major base camp of the trip– Svensby. After an hour and a half of winding North through the fjords, the road ends at a pier. Several cars pull in behind us waiting. Across the fjord we slowly see our transport get closer. The ferry.

Once onboard, we hop out of the car and climb to the second deck. From here the view stands out. Filling our vision from periphery to periphery are massive, ancient rock monoliths the locals prefer to call “mountains”. If these are mountains, I’ve seen only hills before today. Drifting across the arctic water marks our departure from the everyday and into to a destination of myth– trolls, fairies, and danger.

On the other side of the water we make it to our housing for the next few days. We were fortunate enough to reconnect with our host from the year before. Once settled, we take out the salmon and bake. Into the evening the house grows quiet as we scan Windy, Darksky, Fatmap, Gaia, MyRadar, Varsom, and other data sources for intel on our zone. Our plans for the coming days begin to take shape.

Day 4 – Tooth Couloir

I was awoken to Cole’s night terror in the room next to me. Between the midnight sun and his screams, it’s safe to say I slept lightly. In the morning we sipped bitter coffee and ate Norwegian-Turkish yogurt. To complete the meal, I snuck in toast topped with fresh lox. They do it right here. While adjusting to the morning daylight, we scan the weather and discuss line choices.

Today we split in two. Hunter Lee, Stosh, and Cole wanted to do a razor thin, low altitude couloir called New Years Rocket (no idea if this name is official, I just saw someone call it this online). Henry, Hunter Hill and myself had our sights set on the Tooth Couloir. This was on the list from last year, but stormy conditions had led us elsewhere. We set off following each others cars East, deeper into the fjord. Off to the side of the highway we scope with binoculars. It feels feels iffy-– low tide. Henry, Hunter Hill and I continued on. A few miles up the road we pass through two small tunnels and emerge to a pullout. From here our first major mission of the trip begins.

The climb begins with our skis on our shoulders and our feet in the dirt. After a few minutes we latch in on the dirt-brown skin track. The Tooth Couloir is barely visible from the here. Even with the limited view we can see why the name has been given to the line. All we see is a jagged, K9-like wedge bitting into the skyline. We quickly find ourselves in cruise control over slush-wet snow. Hundreds, no, thousands of kick-turns later we arrive at the first moraine of two. This spot marked out halfway point in terms of elevation gain. 2k ft in an hour. We’ll take it.

From this spot we take our first break, adjust layers, and bino the faces surrounding us. The majority of the ridges surrounding us are capped with looming cornices of indeterminate size. There is no foliage for sense of scale here. From our position in the moraine, none of the cornices posed a threat. Closer to the couloir, however, there would be an increased risk. For a short segment there will be an unavoidable cornice path on the way to the couloir. We determine with the stable heat and cloud cover the risk is low. We continue on.

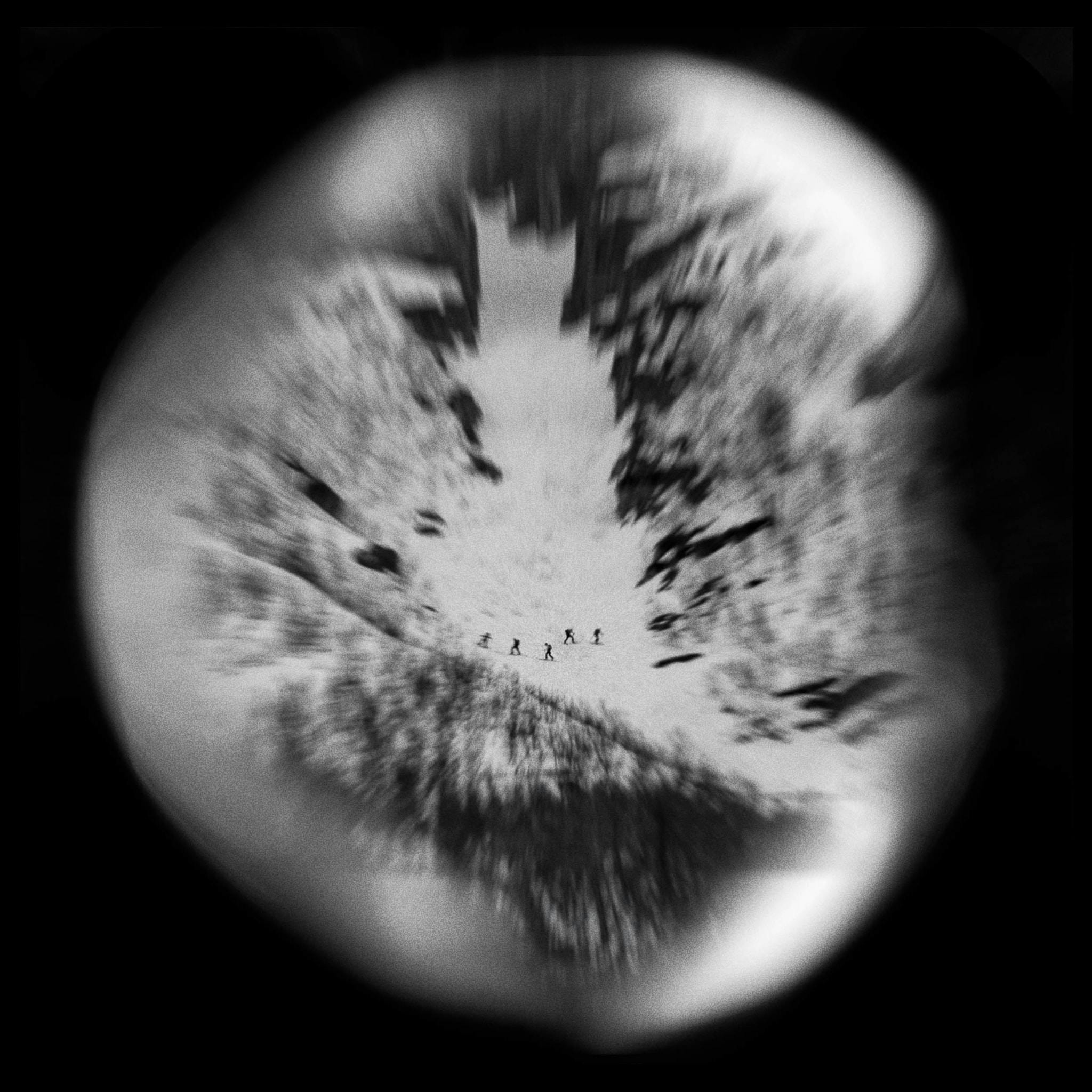

30 more minutes of cruise control and we hit moraine number two. Cresting into the upper bowl, Henry spots a duo approaching the same line as us. From our perspective, they appear as two dark splotches on the face. Only with movement can we differentiate them from rocks. Were we too late? We decide to continue on and re-assess risk as we pass beyond the cornice path and enter the couloir. The skin track set by the group ahead of us wasn’t ideal. But then again, I can make the perfect skin track and no one else can. Isn’t that the attitude any good climbing partner should have?

We switch back again, and again, and again, until we reach a debris field unleashed by a heating cycle in the weeks before. At this point we’re gaining on the duo. Maybe, just maybe we have a chance of catching our rivals. Our focus from here on out is to move efficiently through their skin track in the debris. Soon enough we pop out of the debris and into earshot of the group ahead. We catch up and have quick chat. One of the two was in a ski mo race the day before in Tromsø. I’d be lying if our egos didn’t grow a little after realizing we smoked some racers. They transition at the top of the debris citing that they didn’t wish to ski it. This logic makes no sense to us, since they’ve completed the hard part. They didn’t want to ski it, maybe they aren’t our rivals. Maybe they are embarrassed and didn’t want our leftovers. All that’s ahead is perfect, untouched couloir skiing. Henry, Hunter and I lock in our crampons and start boot packing.

I begin. My main method of trudging through a boot is to force myself into state of suspended mental animation. The thought of booting is unbearable otherwise. The more I think, the more uncomfortable I am. I need to pass time. Halfway up a route is my most meditative state. I count to 10 steps, and repeat until I count to 100 steps. If I get there and there is gas in the tank, I double it to 200. The inner dialog sounds something like this: “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10” “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 20” “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 30” … and so on. Next thing I know I’m in the 1000’s.

The trick is to not think. And bam, we are nearing the top as the powder gives way to wind-buffed ice. Hunter Hill transitions at this point, since split boarding the technical rough ice is, in Hunter’s words, “not the move”. Henry and I are driven by the view from the top, so we continue on. Topping out, the wind funneling through the backside hits me straight across my face. A pic or two later and straight to transition. No one with a healthy sense of wellbeing wants to spend more time than needed up there.

Henry drops to Hunter first. He makes a sketchy cornice hop turn onto the 50º ice and gracefully recovers on his way down. He’d later lose his ski in the good snow. It was sheer luck that his pins didn’t detach on the ice. After meeting up with Hunter, we hit the goods we came to ski. Below us is a few hundred feet of loaded, untracked couloir. The thousands of feet trudging through slush has paid off.

Descending the next 3000ft is a different story. It rapidly grows sticky as a I fall into the back seat and wait to see where my skis take me. Sudden jerks left, right, forward, back, try to crash me. I won’t allow it to happen. At the bottom my quads’ are “gassed” to say the least. The tank is empty but the heart is full.

At the car we transition slowly in muddy boots. Next stop, the nearest grocery store to top up on strange thin breads and lox. Back at the house, we run the sauna. One of the best post-ski activities one can do. I think tomorrow I’ll make the mad dash to the cold ocean water, but today isn’t it. We can only rest.

The rest of the night is spent reminiscing on Tromsø Badet rec center, Camping (the mini golf club), and weather talk. We cook Tex -Mex. The ingredients are pretty similar to what you find at any US grocery store, albeit with strange Scandinavian twists. Norway’s most brilliant invention, worthy of a nobel prize, is the the tortilla pocket. It’s a soft, flour tortilla, pre-formed like a burrito on all sides but one. There is no seam for liquid to drip out. Brilliant. Following dinner, we cook mixed-result brownies and have a lego architecture competition. I like to think my lego sauna won, but the truth is that we have an actual architect with us, Henry. Now I am sitting here, too late, in the dark, in a state of fatigued-content. It’s borderline delirium from the brownie mix and melted ice cream.

Day 5 – Rest

I take it easy with the hope my hotspot would heal. Everyone but Hunter Hill and I went out towards Trollvastinden looking to get into the snowpack and take note. The rain this afternoon seems almost acidic based on how quickly it melted the snow. Village after village has been flooded with runoff.

We head north looking to check out the Peninsula. We park at the northernmost tip of the island. One year ago in this spot we parked to ski Russelvfjellet, the northernmost peak of the Lyngen Alps. Everything up here has melted out this time around. You can almost hike on dirt to the couloir we hit last time. We walk where the pavement turns to dirt, and continue to wander towards the tip.

The rich yellow grass shows signs of thawing life, yet it’s still stark. Everything about the colors of this environment spark some weird cinematic feeling. It’s not that there is an overload of color, no. Instead, the monochrome blue of the sea, sky, and somewhat snow all blend. The rock is deep black, showing no tones but high sharpness. The grass is a rich deep golden yellow, almost skin tone. And the third, rarest of the colors, but one of the most important, is the maroon of man-made structures. The decrepit sheds next to the coastal houses are remnants of a previous generation of builders in the North. Hints of an ancient culture. Each structure is painted with a traditional Norwegian red derived from cod liver. Everyone has nailed the same deep hue. This is no accident. The tradition has emerged from the resources this land has given it’s people. It speckles the psychedelic scenery with hints of an old culture.

While everyone is skiing, Hunter Hill and I start the sauna and the bolognese. As they trickle into the house, I set the pot to simmer and hop into the sauna. Cole had dug out a DIY ice bath from a drainage ditch the night before. The recirculating water is colder than cold. Arctic glacial runoff is much harsher than the stagnant troughs of ice water I’ve dipped into in backyards before. Back in the sauna pins and needles fill my legs as I thaw. Everyone scarfs down a few pounds of my best Italian and we play dice. I’m hoping we get into the alpine tomorrow.

Day 6 – No luck

Another night of rain and warm temperatures make us hesitant to get out. It’s small. Cozy small. Hygge small. Up North from our new residence we try to get into mini golf couloirs. Past the trailhead, none of us wave motivated. Our assumption has been that northern Lyngen would be colder. Our assumption was wrong. We were getting drenched. After discussion, the lox committee decides to travel towards Tromsø (solely for the pool). From the rental I organize logistics to move into residence #2 a day early.

At the pool we were devastated to find diving closed for the day No matter, we sauna, ice bath, and race the slides. On the way out we enter the liquor store to procure tequila, schnapps, and local glug.

A drive later we settle into our new cabin in Lakselvbukt. Birch Log HQ.

Day 7 - Lille Piggtinden

From everything I have seen the Lakselvbukt valley captures the essence Lyngen. Dr Seuss could have gotten away with drawing these mountains into reality and I wouldn’t know any better. From the road the range shoots up directly to our East. The frost-white caps indicate that these are some of the highest peaks in the zone. Wet air coming from the Arctic in the North rises as it slams into the mountain range. Lower elevations are protected, but the highest peaks bear the brunt of the winds. The wet air contains supercooled moisture that doesn’t have particulate to condense onto. As the water touches the rocks of the peaks, it immediately freezes into a hard ice, known as rime. The rime layer contains clues that indicate the direction of recent wind events.

A year ago we skied a famous couloir in this valley known as the Thomas Couloir. From Thomas, we could see a prominent peak across the valley asking to be climbed– Lille Piggtinden (the Pig). The upper few hundred meters of The Pig stands isolated from its surrounding ridge line. From the valley in the East, two obvious couloirs are in view. There is a fair bushwhack approach for several hundred vertical feet before climbing onto the couloir’s exiting shelf. In a single quiet line, we trudge in it’s direction. Rain seeps into our jacket seams before we can get above the freeze line. An hour later we find ourselves with a choice– A. Go left at the Y and ski the more prominent, yet constricted line. Or B. Right into non-line-of-sight territory. A gamble, but potential for payoff if the terrain around the bend is favorable.

Stosh, Cole, and I split from the rest to explore left. We’ve been studying this line, known as the Saggečohkka Couloir, for months now. The rain continues as our kick turns increase in frequency. Surprising, it wasn’t forecast to be this wet this high. At least not by the model we’ve been relentlessly checking. Nearing the choke, any visibility of the peak has gone. The inside of a pingpong ball encircles us. In a moment of silence, Stosh hears the rush of sluffing snow in the clouds that surround us.

Between the wet, the warmth, and previous observations that day, we chalk it up to the heat loosening the snow from a light dusting the night before. We spend no time waiting around to traverse the potential debris path beneath the couloir’s constriction. From the other side we wait, listen, and eventually observe a larger wet sluff pile funneling into the rock choke. That’s our final straw.

Our decision leads us to alternate lines, ones with minimal constriction and exposure. As a group we aim for movements to the left of the initial line. From a shelf above and askew to the choke, we rest. Soggy with cold hands, hot heads, and cement legs, we look at each other in defeat. Today was not our day. Somewhere along the way we had been tricked into not having a good time. That’s not why we came here. A short transition later, we descend through waxy, sticky snow. At the car Cole, Stosh, and myself strip down to our base layers. We appear as if we just went diving at the Tromsø Badet.

In the sauna we watch as the clouds become more dense. Rain gives way to snow. The forecast is favorable. Thick flakes plant a seed of hope for the days to come.

Day 8 – Quarry

Our plan from the start failed us. As we drive towards a new zone across from The Pig, the terrain isn’t looking promising. The moment our target ridge line comes into view I scan it with bino’s. Even without contacts, I can make out massive cornices above each line. The wet snow from the night before had loaded cornices and doubled up the rime. We head North.

An hour later, we pass through a small quarry town in view of our first home of the trip. Our previous stay is a short swim away, maybe even a nice rock-skip, but still a day’s drive. Such is the nature of seaside villages and mountain towns. The road dead ends ahead of us into a scattered assortment of huts and mining equipment, remnants of this, and many other mountain towns, previous lives. This marks the start of arguably the most popular line in Lyngen– the Godmother Couloir. Popularized by guidebooks and Instagram locals, the Godmother stands as one of the most picturesque and lengthy couloirs in the region. I won’t go into too much detail, there are plenty of resources out there [add various links as footnotes here]. In my opinion, it’s overrated. The real draw for us to come to a dead end quarry is to scope a less travelled line– Store Fornestinden’s West Couloir.

Few records exist of the line on the internet, though there’s hope that more than a few have completed it. Months of digging yielded only a single video on the internet. As far as the digital world was aware, this was unskiied territory. We found it in the guidebook, nay, the bible known as “The Lyngen Alps (Norway): Skiing / Climbing / Trekking Guide” by Sour Nesheim & Elvind Smeland. Buy it, read it, and reread it. Sour and Elvind’s treasure trove of routes and descents is our gateway to the real hidden gems of the region. Fornestinden West Couloir is a massive couloir with technical challenges in the line. I snap photos from the parking lot of this line, barely visible and several miles away. We turn around.

The day has turned sour and any inclination to ski a burly line is fading. On the way back, we park at the quarry surrounding the road. Picturesque, so it’s worth a stop. Our lizard brains kick in around old infrastructure. It draws us in like Legos once did as we were kids. We wander. I am no urban skier, but I can’t resist when I see the closed conveyors, dirt piles, and tubes. I channel my inner Alex Hackel. Henry and I put boots on and carry our skis out. Henry, an actually skilled park skier lines up some wood crates as a ramp to hit a railing. He makes it look good. We then wander up to the belt conveyors for my turn. One conveyor looks ripe for riding. The rock pile it has formed doubles as a landing. I get up, push off, and… Nothing.

I’m stuck. The dusting of snow is no match for my weight and the rubber of the belts. In defeat I shuffle my way to to the end and drop. Like a stubborn grom, I scour the quarry for a redemption hit. On the ocean side of the road, the quarry extends a pier out meant for ships to load. Clearly closed with no one around, I’m drawn to climb to the end. I’m halfway to the tip when it dawns on me how unsuitable this path is for foot traffic. The pathway is only two 2x4’s wide. Hell, my Armada Whitewalkers are pretty much two 2x4’s. From the end, I balance to lock into my bindings. I must take extra precaution to avoid dropping a ski into the arctic waters below me. Hunter Hill flashes the universal “O” for filming and I push off. It’s slow going to start, but the length of the pier leaves plenty of room for acceleration. Soon I find myself using arms and drag to control direction. With no edge to turn on, it’s a game of human shuffleboard. Adrenaline-fueled bliss.

Into the car our wet skis go. Out of the quarry, our ski egos. With a half day to spare, we return to Camping Tromsø.

Day 9 – Fugledalsfjellet

The first alarm does nothing for me this morning. Still processing Aquavit liquor and overpriced pilsners, my body fights me to get another hour or two of rest. Camping, everyone’s favorite club, went late. By the time we left to drive home, the sky was already blue. It means little in a place that sees the sun rise and set in the same hour.

Lee, Stosh, and Cole rally to get out earlier than us. The forecast has lined up, and the rain gave way to more consistent snow overnight. We suspect that Westerly faces fared better with the overnight winds.. The plan: Fugledalsfjellet West Flank. Several hours after group one’s departure, Hill, Henry, and myself begin our journey from our cabins countertop outpost. Lox and Giflars make a Hunter happy. We disassemble the decor of hanging jackets, gloves, and skins and pack our bags. We head North.

Our target face isn’t visible from the road. Skin tracks set earlier that day by the others indicate where to begin. Too much trust in those three, if you ask me. Soon after cresting the first hill, the forest gives way to a frozen river bed. The river points us toward a breathtaking panoramic view. To the left, Fugledalsfjellet. Massive on its own, but nothing compared to the surrounding peaks. To the right, Holmbukktinden. A solitary rocky face, reminiscent of Mt Doom, surveying a frozen Mordor. There is a partial line on the peak that looks skiable. Up the center of my view stands Jiehkkevárri, the tallest of the Lyngen Peaks. It’s simply huge. No other way about it. Most popular lines on Jiehkkevárri pass over the top, avoiding any real terrain. To climb it would be an accomplishment, yes, but we were hoping to avoid odysseys through the mountains this trip. The draw of Lyngen is Alaska-style peaks with little to no approach.

A few hours of skinning and we find ourselves on a wide open face in Fugledalsfjellet. This is a simple line. No technicalities, no bottlenecks, nothing to make our day harder. Last night’s liquor is doing more than enough. Every n minutes we tag team to break trail. An hour later we crest a wind-stripped rocky ridge. Skis come off, crampons go on. We hike over rocks for several minutes before falling back into knee-deep powder. Skis go on, crampons come off. If I face one more transition I’m going to lose it. Eventually the tracks stop, and a rock protects us to eat a snack and turn our focus downward. What follows is 10 minutes of bliss.

Hill and Henry cruise down the face. The few ridges on the slope shape beautiful wind lips. The duo take turns slashing them into oblivion. I document. They continue without hesitation for minutes on end. By the end of their run, they barely register as specs in my vision. A call on the radio signals for me to go. While some opt for the traditional powder 8 approach, I chose to practice the dont-fucking-turn approach. I want to be Candide. The snow acts as a massive airbag, protecting me from any potential fall. This mental security leads me to ride aggressively down the whole slope. Riding into Henry and Hunter, I try my best to make a pow butter. My cherry on top. That was a top 10 run, no doubt. Until the events that followed…

You see, I bought a drone for this trip. The jaw-dropping panoramas, hidden waterfalls and stunning fjord views I experienced last year forced me to buy the perspective enhancing, commercial defining piece of camera tech. I did my best to read the manual and practice a few times, but I had too much faith in the technology. From the top, I filmed the others from the tiny remote screen. Eager to get my own clips in, I set the active track. It worked, at least the first 15 seconds of the run while I checked. But, somewhere between looking back at the drone and opening up to mach 1, the device disconnected. I pull the remote out at the bottom to try and find it, but the remote showed no signs of drone life. Sh*t.

The documentation states that in any unexpected event, the drone is to fly back to its home point and land on its own. So, if it disconnected, it should find its way. The problem– its home is its takeoff point. About 2,000 vertical feet above me. I stand silently for two minutes. Do I give up on the drone now, or schlepp myself back up, hungover, to the takeoff point. I start going. I tell the others that they need not follow along. No matter, the boys rally. Begrudgingly we walk.

An hour later we near the spot. Nothing. I search left, right, up, down, but nothing. Just perfectly smooth, white, untouched snow. All for nothing. In defeat, I watch the others ride another line and enjoy themselves. I on the other hand, make half the turns as last run. Pissed off and on a mission to go fast, I open up recklessly. The sun lit snow fades into shadows. In flat light full gas, I look down as my feet float above the milky void. Sh*t. A second later I slam into a compression and try to hold on. I eat it. At the bottom, embarrassed, and on video, I smile. Who cares about the drone. That was another top 10.

Back at the cabin, I file an insurance claim on the drone. You see, I expected my recklessness would lead to the device lost or broken. My prepared unpreparedness has paid off. Around the dining table we strategize for the next day. Today gave us confidence in the snows stability on shaded West facing aspects. With limited options, I scan my collection of lines built with days of research. For the nth time I bring up the big kahuna Fornestinden. I mention it partially as a joke, but after a second thought, it hits all of our criteria. Western aspect. Shaded, especially in the morning. Rather protected with only a few places for cornicing above. We discuss. Cole’s eyes grow with the realization that our moonshot might happen. Tomorrow, Cole, Stosh, and I aim to ride Fornestinden’s Northwest couloir.

Day 10 – Fornestinden

Today’s story begins in a stone quarry, long forgotten, frozen in time and hidden beneath the shadows of the peaks a fjord away. In an act of anarchy, we leave the car 10ft from the only no parking sign within 10 miles. We had limited options. For several minutes we walk on rock pikes next to machinery. Exiting the industrial site, we receive a nod from the only person around. I can’t get a read on him. Either he’s anxious, or rather dreadful that we might not come back, or he really couldn’t care less. Soon the rocks turn to an ancient snow mobile track laid several storms before us. By this point it barely registers.

One step, two step, we inch closer to Shangri-La. We pass bushes, shrubs, and twigs. As we continue to ascend, we trade the light foliage for stark, empty faces. Eventually, a river crossing leads to us topping out over the moraine that blocked our view of the valley ahead. As soon as my eyes peaked over I could see the stunning landscape of our day ahead. Bliss.

One step, two step. As the foliage gives way to raw alpine, the real monotony begins. Every 15 minutes one of us stops, thinking we’ve identified the landmarks studied the nights before. Every 15 minutes, we’re proven wrong. I’m beginning to think it’s an excuse for Cole to slow his pace. The run out of the chutes above us are massive. Bigger than most I’ve seen before. We ascend in a straight skin track, cutting across the fans of snow like a razor blade. This must the biggest single skin cut anyone has done without a kick turn. One step, two step. We are now hours into our mission and only getting to the entrance of the line. The higher we ascend, the more me push our limits of how steep a skin can be. We do this knowing that 10ft of booting up the face is worth the same energy output as 50ft of skinning.

At some point the mountain wins. There never was a chance for us. During the transition, the Nordic candy, lox, and salami comes out. Hvar (whale) is actually worth a try. I take first boot duty. My mission is to top out the current chute that feeds our into our main line. Consider this our shortcut, one that takes 30 minutes to reach. I force the others to take lead. From here, we must shuffle perpendicular to the slope to get into the main chute. Below, cliffs of mysterious heights. There’s no telling without visibility of any ground below. Cole takes over and puts on a herculean performance to break trail. Some time later Stosh goes ahead. No matter our placement, it’s deep. Each step takes the effort of scaling a flight of stairs. It gets steeper.

We round a corner and reach a spot that feels totally surreal, surely something this steep can’t hold snow. Yet here we are. I take over. The couloir meets it’s bottleneck, the snow gives way to rocks and ice. Powder turns to blue ice hiding beneath a light dusting of snow. I bring the ice axe out. Nothing makes me feel cooler. The others watch from afar as I go ahead. I work quickly in the bottleneck as to avoid time in such a vulnerable position. I make it to a safe zone and call the others up.

We continue the booting slog. As the elevation increases the view widens. Peaks we had only previously seen from the West can now be seen from the East. Even from these heights, we can only see a sample of what Lyngen is. The peaks surrounding us provide endless spines, lines, and cliffs middle school Hunter could only dream of. I take a look down and see the others. Our boot-packed staircase seems endless. Our trail of steps gets thinner and thinner until the footprints blend together. Following the trail of stairs, it eventually turns a corner and disappears, hundreds of feet below and on an impossibly steep slope.

One-by-one, the bonk hits. Utter fatigue. I was victim earlier on, but I survived with the help of my Secret Bonk Juice™ and a little salami. Stosh feels it. As he slumps for a minute, Cole tags back in. He makes solid progress for 30 minutes, until he feels the fatigue as well. As I catch up with him, we now face our options to complete the climb. To the right, a possible opening in the ridge to top out. Upon closer investigation, it’s a dud. The rime on this line is too thick and seems to go over-vert. To fall here would be to fall off the side of the mountain. Not something we are prepared for today.

To the left, the line documented in past climbs. Although today, it presents different risks. Near the top, the route elbows right under a huge face of rime-splinted rock. Only moments before, the sun had found its way to this cliff band. The heat had melted some snow and caused a waterfall of ice. In the silence we hear a rainstorm, but instead of water it’s rock hard. Cole and I make way to get closer, finding safety under the last possible hideaway from the rock-rain. Stosh makes his way to us. We discuss. Cole and Stosh decided to peek into the rain quickly, seeing if the right elbow gave way to top-out on the summit. I scope from afar, keeping watch for larger chunks falling. Both of them begin to struggle in the thick of it. At the choke in the elbow, there has been an under-snow den now uncovered by the weight of each other. Each step sank them deeper into a tunnel of unknown depth. They try several approaches, but nothing works. They cut their losses and return

We accept the failure to top out. But that’s not why we’re here. We’re here to ski, and we have reached the top of the skiable line. Below us– several thousand feet of untapped couloir. I take the first few turns to get in photo position. After my few turns, I can only yelp in joy. This sh*t is real! Cole descends next. He laces a beautiful line making quick work until safe above the bottleneck. Stosh next, throwing in a small cliff to spice it up. I put the camera away and let my feet guide me. The best few turns of my life. Steep, fast, powder. It’s euphoria that can’t be understood by those who haven’t had it. I lead the pack through the choke. It’s tough, but we make it through. The next 1.5k feet are spent trying to differentiate the icy faces from the soft. Several minutes of quad-burning and we are spit out into the endless apron.

From the bottom of Fornestinden, we look back up. Thousands of feet above we can barely make out our tracks. Cole demands, “We have to play down how amazing that was when we get back.” Sorry, I’m blowing our cover. That was a life-defining mountain. Together we snack, take our time, and suck in the view. We point out lines through the valley we’ve only seen in books. Blissfully we trudge miles back down to the quarry. On the way out, we nod back to the worker from this AM. We drive back. We get home to the others shirtless grilling outside in the late evening sun of the Arctic.

Day 11 – Thomastinden

Cole wakes me up. A few of us were up too late watching The Equalizer. Denzel get’s ‘em good. It’s late in the morning, and Equalizer 2 is on in the background while I sip my burnt coffee. I had no plans going into today. Any climbing from here on out on the trip is a victory lap in my mind. Together we stare at the weather, avalanche reports, and Fatmap. The others who hadn’t climbed our mission the day before were eager to try a line Cole and I had done the year prior. The Thomas Couloir.

Sandwiched between two peaks, Thomastinden and Store Lakselvtinden, the couloir splits the Ridgeline.Last year we had chest deep storm skiing in the zone, albeit with negative visibility. We decided not to top out of due to wind events in the storm. This time, there was nothing but sun. The group rallied, and their energy fed me. I took off with them.

We park at the church. Several cars have clearly parked for the same mission. No surprise, this is one of the more trafficked zones in the region. The tour starts mellow, splitting a sparse forest. On the way we pass a few traditional structures buried in snow. One creek crossing, mellow enough to keep our skis on. The slope steepens. For the first hour, we quickly gain altitude. The sun bears down on us with its full power. I take my jacket off first, then my shirt. The others don’t see until we pop out on a shelf looking up at our line. I top up on sunscreen and snacks, then we continue.

Another 45 minutes and we find our next checkpoint. From here, the couloir splits into two. Last year we skied both, but today’s mission is on the right. Two groups are up ahead, one partially up the gut, and the other topping out. We transition. One-by-one, we scramble up on the tips of our crampons. Mixed snow means for moments of efficient climbing, and then unexpected punches waist deep in the snow. It’s slow, but after yesterday it’s bearable. One of the groups above skis directly over us and cast a wave of snow.

An hour later, and 2000 steps counted aloud in my head, Cole and I pop out the top of the ridge. From the top of the line is a plateau, spanning about a mile deeper into the mountains. To our left, a beautiful secondary couloir leading to the top of Lakselvtinden. We turn the opposite direction, and follow the skin tracks of a group in the distance. Soon enough we catch up, right as they are reaching our new summit– Thomastinden. From here, the world seems small. Clouds cast shadows into the valley below while we cast shadows onto the clouds. From here, there is a clear view into a massive valley I have only seen in books. The lines we have studied lay before us. Ellendaltinden, Big Chasm, Nallangaisi. Our group huddles up next to the French skiers. We chat through broken French and English. They explain how a helicopter we saw earlier in the day picked up an injured skier on the Lakselvtinden Couloir across from us. We chat climbing, gear, food, and culture. Mountain people are funny– despite language and cultural barriers I often find myself having more in common with someone from a mountain town in a far-flung corner in the world than I do from many people in my country. The love and respect for the ethereal power of the mountains is a universal experience. We find balance and peace perched atop of a peak of rime.

We let the French go ahead. Henry, in an act of respect and admiration, brings out a small bag of his grandpa’s ashes. Silently, we let him pay his respects before letting him go. A beautiful way to get laid to rest. One by one, we transition and depart down. Several thousand feet below the summit, we catch back up with the foreigners. They had stashed paragliding equipment from the bench below the couloir. We ask if we could ski under them, and they agree. The rest of the run had me looking up as if I was bird spotting.

Back at the house, the sauna is ripping as the other Hunters had tended to it. We roast. We jump in the fjord. We cook brownies and drink pilsners. Equalizer 2 comes back on, but I don’t make it to the end without crashing.

Day 12 – Big Chasm

The other boys are toast. Without the legs in them for a massive mission, they search for a nearby option. Together, they scheme up a plan to ride a short couloir seen from our day on Fugledalsfjellet. Not for me. The night before, I had studied images from the summit of Thomas. Across the valley lies the Big Chasm. A massive, steep, intimidating couloir. The snow is stable, the overhead danger is low, but the long approach and huge vertical gain makes the others turn away. I venture up the valley, curious to just see it up close. Scoping for a future trip?

From the peak the day before, I snapped pictures with my biggest focal length (not enough). It looked like some wind-swept ridges in the valley, but up on the apron of Chasm, not much. It seemed an acceptable mission. My solo approach went quickly, as I had set Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History to play a repeat episode in my ear. Next thing I know, I’m miles into the trek. Hours had passed, but my mind had time travelled. In from of me stands Ellendaltinden. Huge, beautiful, but not the objective for the day. I follow the valley right. The wind scoured waves I saw from yesterdays summit proved to be more annoying than expected. Persistent winds pick up ice shards and fling them in my face for hours. Sandblasting. The waves create pockets of loaded powder, following by a surface that represents an ice rink. The going is difficult, but I manage.

An hour later, I fight my way onto the apron of Big Chasm. As I pass over waves of wind formations, they crack and break off, sending themselves high speed over the rime-ice. It’s a scary proposition to be on these conditions hundreds of feet up a couloir. Not worth it, especially as a solo traveller. Not the environment to raise my risk. I turn around, and make the long journey back through the valley. In the car, I bump Provoker on max volume. At home we catch up over stories, jump in the water, and finish Equalizer 2.

Day 13 – Tromsø

Back in the port city of Tromsø, the boys get together and rally for a sauna on the dock. On the shared sauna bench, locals tell us about their lives in Tromsø, and the draw to the land. Money that once came in from fishing has transformed into money from arctic tourism. There is a new group, however, backcountry skiers. Much like places like Jackson, Aspen, and Mammoth, the locals have a healthy fear of the backcountry. They try to re-teach this lesson, but we know. They share stories of beers, cigs, and the best club of the small city center. I think a gun and healthcare joke came up too. The barren arctic gives. We drop the rental cars off and say goodbye. Each of us headed to different destinations. Maybe I’ll reconnect with them next winter, who knows. With my risk quota filled and my ego fatigued, my time in Lyngen comes to an end.

Links & References

👉 If you enjoyed reading this, follow my Instagram to stay updated with future projects.

Words by Hunter Bryant

Photos by Cole Mogan & Hunter Bryant

Edited by Jack Chase & Hunter Hill

Strafe Outerwear

Strafe Outerwear– the best gear in the game and good people. They supported our trip and we couldn’t be more grateful for the help from Victor Major and others at the company.

The Lyngen Alps Skiing, Climbing, Trekking

“The Lyngen Alps (Norway): Skiing / Climbing / Trekking Guide” by Sour Nesheim & Elvind

Pust.io - Badstue | Badeopplevelser | Yoga & meditasjon | Mat

Pust, the floating sauna

Home - Tromsøbadet

Tromsøbadet, the world’s greatest rec center

Cabin in Lakselvbukt · ★4.75 · 2 bedrooms · 6 beds · 1 bath

Our Airbnb in Lakselvbukt. Frank and his son were great hosts.

Cabin in Lyngen · ★4.95 · 3 bedrooms · 7 beds · 1 bath

Our Airbnb in Svesby. A pre-WWII cabin retrofitted with a modern half.